Asia’s ‘Boom’ of Difficult Memories: Remembering World War Two across East and Southeast Asia

Daniel Schumacher, Originally featured in: History Compass, 13:11 (2015): 560-577

The ‘Great War in Asia’ ravaged large swathes of the region between 1937 and 1945 and claimed over 30 million lives, injuring and displacing an even greater number of people.[2] In 1941, it merged with the war in Europe and formed an important theatre of a truly global conflict. Emperor Hirohito’s surrender message in mid-August 1945 not only signalled the end of eight years of large-scale fighting in mainland China and of three-and-a-half years of brutal occupation of virtually the entirety of Southeast Asia; it also ended Japanese colonial rule over Taiwan and Korea, which had lasted almost fifty and thirty-five years respectively. It furthermore ushered in the end of both the Japanese and eventually the European empires, and a radical realignment of the geopolitical landscape in the context of the emerging Cold War.[3]

The legacies of what can rightfully be labelled one of the central and most devastating events in the twentieth century history of Asia permeate its post-war social, political, and economic order. Many of these legacies remain highly contested, overlap with the memories of subsequent conflicts, and significantly strain domestic and international relations throughout the region to this day. Local governments and interest groups almost routinely enlist its numerous and diverse legacies in the politics of remembrance while the popular media often readily chime in and fan the fires of controversy that still smoulder over issues connected with World War Two.[4]

Despite its enormous significance, the war in Asia has long been virtually absent from mainstream historiography. The study of war and memory has been dominated by a nearly innumerable amount of publications on Europe or ‘the West’, which systematically sidelined the Asia-Pacific theatre of World War Two (and the interconnected events of the Second Sino-Japanese War).[5] So much so, in fact, that in 2004 – almost 60 years after the end of the conflict – Bayly and Harper still thought it necessary to write about its ‘forgotten armies’ in former British Asia.[6] Even the events in the Chinese theatre, which resulted in the greatest number of casualties in Asia, have, as Rana Mitter and Aaron Moore observe, “remained in the shadows [...] until recently”,[7] both in Asia itself and in the West. This is, in part, due to pragmatic reasons. Many archives remained inaccessible to researchers for decades. Eyewitnesses of the war often found it hard to talk about their experiences or commit them to paper. And when they did, they found themselves misunderstood by younger generations or saw their voices marginalized by regimes which themselves utilised the war’s legacies to underpin their own legitimacy. Publicly paying homage to the sacrifices of many veterans and that of civilians or adequately addressing difficult questions pertaining to perpetratorship or collaboration fell by the wayside.[8] In the immediate aftermath of the war, as Morris, Shimazu and Vickers argue, reconstruction was the predominant concern for many Asian countries, not remembrance”.[9]

In the 1980s and 1990s, numerous socio-political and economic shifts both in the region and globally caused many societies in Asia to publicly reflect on established categories and frameworks for identification. An integral part of this process was the significant revamp of public forms of commemorating the events of World War Two by both state and non-state actors. This, again, contributed to rising tensions over interpretations of the wartime past in Asia and triggered a burgeoning academic interest in the topic. Studies have largely applied a post-war nation-state focus and often follow a comparative approach. They commonly divide the region into two distinct spheres of analysis. On the one hand, they focus on East Asia as the core of Japan’s former wartime empire, covering South Korea, Taiwan, mainland China, and Japan itself. On the other hand, they compare select recollections at its periphery in Southeast Asia, and devote special attention to the Malaysian peninsula.[10]

Taking this as a starting point, it is the objective of this article to provide a broad and necessarily limited overview of the current research [11] on the different and highly complex forms of public commemoration of the conflict that greatly impacted East and Southeast Asia between 1937 and 1945.

The long end of war

Public recollections of the war years remained limited throughout Asia for decades. The reason for this may lie in the fact that for many countries the surrender of Japan did not result in the end of violent conflict or the smooth transition to self-rule.[12] In 2001, Fujitani, White, and Yoneyama were among the first to reflect academically on the Perilous Memories that formed in different parts of post-war Asia. They exposed the region’s highly- fragmented make-up by looking at the many layers of remembrance that had developed and that mirrored the myriad ways in which the war and its rupturing effects had been experienced.[13]

Indeed, in many instances there was a very long end to World War Two. Domestic civil strife that had been interrupted by the Japanese invasion, as in mainland China or Burma, returned with a vengeance in the form of civil wars not long after Japan had signed the Instrument of Surrender. These civil conflicts profoundly shaped the political landscapes both domestically and in neighbouring countries.[14] In China, the communist victory in 1949 gave birth to a People’s Republic under Mao Zedong where remembrance of the significant war efforts of the nationalists were now politically untenable and consequently marginalized. It furthermore forced the latter to flee to Taiwan where Chiang Kai-shek established a mainland Chinese-run regime under martial law and promoted Chinese nationalism. This provided opportunities for identification that proved meaningless for many local Taiwanese whose lives had previously been shaped by half a century of comparatively benign Japanese colonial rule. The War of Resistance against Japan as fought by Chiang’s Guomindang (GMD) forces on the mainland now became the official historical reference point for the Chinese state on Taiwan.[15]

In the wake of the 60th anniversary of the end of World War Two, David Koh revisited the Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia and further demonstrated the gains that can be won from also including territories that escaped the war relatively unscathed.[16] Among them are Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and the Indian subcontinent (excluding Burma). Public remembrance of World War Two is virtually absent in these countries as other subsequent conflicts became the key events included in national (foundation) myths. The Second World War brought to a boiling point many pre-existing political, ethnic, and religious tensions in the entire region, many of which had their roots in or had been further cultivated under previous colonial rule. Hence, protracted armed confrontation with returning European powers in Southeast Asia – such as with the British in Malaya, the French (and later the United States) in Indochina or the Dutch (with major help from Britain) in Indonesia – almost seamlessly continued the anti-imperial struggles local groups had previously fought against Japan, and which were now directed against a new enemy.[17] In the case of Vietnam, this struggle only ended in 1975 with the retreat of American forces and the unification of North and South Vietnam under communist leadership. In the case of Korea, the end of World War Two did not bring eventual national unity, but division. The Korean War of 1950-53 divided families on the peninsula indefinitely and created a drastic asymmetry in economic and social development over the following decades. Remembrance of the 1937-45 events took on a subordinate role.

Thus, as Tim Harper argues, if we seek to understand the different ways in which the war in Asia has been remembered, forgotten or completely reframed, we may need to think of it, and World War Two more generally, in a less self-contained fashion; an approach that has yet to be adopted by other researchers in the field.[18]

Asia’s ‘memory boom’

The 1980s and 1990s marked a significant departure from previous modes of remembrance in Asia with many actors in the region revisiting their wartime pasts. History activism experienced a surge, school textbooks were rehashed, and numerous monuments, heritage parks and museums dedicated to the war in Asia were remodelled or newly constructed.[19] Jager and Mitter assign the end of the Cold War particular significance in this process, while the 50th anniversary of the end of World War Two, political liberalization movements in several Asian countries along with the region’s growing economic integration have been identified as further reasons for this shift.[20] The trend accelerated in the 2000s and has been correlated with the region’s hike to economic prominence, the rapid increase of tourism flows across Asia, and the industry’s increasing diversification to include ‘places of pain and shame’ that serve to educate both a domestic audience and the global culture/heritage tourist.[21] The re-evaluation of wartime representations is thus closely intertwined with the evolving public discourse on heritage and its conservation, and therefore with the (re-) formation of identity in the region.[22]

This ‘memory boom’, of what appears to be Asia’s very own “generational shift from testimony to commemoration”,[23] has been the subject of analysis from a number of different perspectives and disciplines. The literature, however, often adopts established theoretical frameworks as applied in the field of memory studies from largely European and American case studies. Maurice Halbwachs’ concept of ‘collective memory’ has been widely received and so have Pierre Nora’s (highly Franco-centric) ‘sites of memory’ and criticism thereof. Concepts such as Marianne Hirsch’s ‘postmemory’ or Levy and Sznaider’s ‘cosmopolitan memory’ that place the globalization of Holocaust memory at the core of their investigations have furthermore gained strong footholds.[24] It appears that Aleida Assmann’s view that “over the last decade the conviction has grown that culture is intrinsically related to memory” and Alon Confino’s assessment that this profoundly shapes how we perceive of our contemporary world have gained currency in the literature on war and memory in Asia as well.[25]

Asia’s memory boom also revealed that the increasing global accessibility of alternative opportunities for identification – of cultural or political principles – contributed to a globalization and ‘common patterning’ of national commemorative practices.[26] Especially in East Asia, narratives of victimhood became core components around which national narratives gravitated.

Victims all around

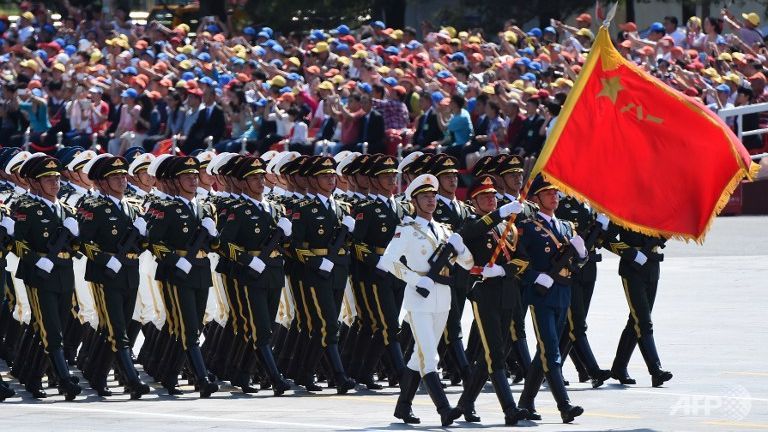

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) stands out as a prime example of top-down efforts to create a national victimhood narrative. In recent years, there have been a number of path- breaking studies that illuminate the war from a Chinese perspective.[27] In his 2012 study, entitled Never Forget National Humiliation, Zheng Wang delineates how historic references have fed into and shaped Chinese politics and foreign relations. He argues that amid severe challenges to its legitimacy in the wake of the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the collapse of the communist bloc with the end of the Cold War, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attempted a rewrite of the official narrative with the 1991 Patriotic Education Campaign. This rewrite swapped a national narrative that had previously centred on class struggle, revolution, and victory against the fascists and nationalists for one familiar from the late Qing dynasty and early republican era.[28] This narrative placed China’s modern history in the context of a century of humiliation by external powers, ranging from the British in the Opium Wars to the Japanese in World War Two.[29] Wang argues that the PRC leadership willingly sustains this victim-narrative in order to draw domestic political legitimacy from it by ‘attempting’ to overcome it. Tony Brooks’ inclusion of non-state actors who have actively partaken in and shaped the commemoration process is in tune with an emerging trend of breaking with the literature’s sole focus on the state and its politics of remembrance.[30] We should, however, be careful and take note that these actors cannot always be clearly separated.

The memory boom in China is also representative of a trend in memorialization practice that adopts both the domestic and international public spheres as the main arenas for commemoration. In the PRC, this has most recently been symbolically underlined by the introduction of two separate memorial days in 2014 – one commemorating the victory over Japan and thus the departure from a century of humiliation, and one commemorating the Nanjing Massacre, cementing China’s role as a victim by recollecting its very own ‘Holocaust’ and tapping into the globalization of the latter.[31] Both days are also used to situate the country as a significant power on the world stage by presenting them in the context of similar ceremonies observed internationally, such as Britain’s Remembrance Day or the International Holocaust Remembrance Day.[32]

The PRC is, however, not the only country in East Asia where what Jie-Hyun Lim calls ‘victimhood nationalism’ is a central component in wartime representations.[33] Since its surrender in 1945, Japan has succeeded in building a narrative that portrayed the country as victim, not perpetrator, in the conflict. It revolves around the notion that Japan (under an ‘innocent’ Emperor) had been rescued from militarism’s embrace by the United States and set on the path to peace, democracy, and economic recovery, mirroring a new set of values for the post-war state that were fostered by the occupying US forces.[34] Memorial parks constructed in the atom-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the late 1940s and 1950s conveyed this message of peace and focused on the suffering of Japanese civilians at home rather than the suffering inflicted by the imperial military abroad.

However, authors like Peter Siegenthaler or Kazuhiko Togo remind us that Japanese society has, in fact, been much more divided on the country’s former role as an imperial power, and on issues of atonement and responsibility for the war it waged in Asia.[35] More moderate voices, such as that of Prime Minister Murayama, sounded reconciliatory tones in the mid- 1990s. On the occasion of the half-centenary of the end of World War Two, Murayama for the first time publicly articulated a ‘heartfelt apology’ for the immense suffering caused across Asia by Japan’s ‘colonial rule and aggression’.[36] This baseline for the official position on the war for subsequent Japanese governments has since frequently come under attack by revisionist politicians whose actions often shape outsiders' perceptions of Japan as an utterly unrepentant country. Repeated official visits to Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine [37] by Prime Minister Koizumi in the early 2000s exemplify this conservative backlash in Japanese politics.[38] This has, in recent years, been further corroborated by increasing territorial disputes over the Dokdo/Takeshima and Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and the denial of Japanese war crimes by current Prime Minister Abe.[39] At the same time, the apology and compensation offered by the Mitsubishi company in an unprecedented gesture to former Chinese forced labourers in July 2015 equally illustrate the forces that run counter to revisionist voices.[40]

In Taiwan, the process of democratization that began in the late 1980s allowed for a gradual shift from a GMD-imposed victor- to a victim-centric narrative. Shogo Suzuki points out that political movements were able to gather pace that challenged the GMD’s view on history and exposed atrocities committed by Chiang’s post-war regime, while at the same time casting a more favourable light on Japanese colonial times, linking them more immediately to Taiwan’s twentieth century modernization.[41] The 2/28 Peace Memorial Park and Museum in central Taipei, opened in 1997 and deliberately akin in name to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, physically articulates this sea change in public commemoration and the quest for a distinct notion of ‘Taiwaneseness’.[42] It provides the Taiwanese with an opportunity to identify as victims, mainly under Chiang’s reign in the post-war years, but more recently also as victims of the Second World War, as a 2015 special exhibition in the 2/28 Museum showcased. It accompanied a public event to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the largest US air raid on Taipei in May 1945, which killed more than 3,000 residents. Remembering this episode allows breaking free from the GMD’s former focus on the victory over Japan and from the intentional forgetting of Taiwan’s past as a Japanese ‘model colony’.[43]

In South Korea, a practice of glossing over the history of Japanese colonial rule – an experience nowhere nearly as benign as in Taiwan – had initially formed an integral part of commemorating World War Two as well. In his analysis of South Korean school textbooks, Hyun Sook Kim describes the commemoration of World War Two as being integrated into a ‘hypernationalist ideology’ that portrayed “Korea as a colonized national-ethnic subject”,[44] and imagined it in Confucian patriarchal terms. Public remembrance of groups that could threaten this image was suppressed, notably the so- called ‘comfort women’, or ianfu, who had been recruited predominantly from Korea, but also from other parts of Asia, usually by force or under false pretence, to service the Japanese military as sex workers.[45]

The ianfu’s fate first came to the public’s attention in 1991 through a number of personal testimonies as well as subsequent films, publications, law suits against the Japanese government, and the redress movement by former comfort women from Korea.[46] Varga and Kim find that in South Korea the comfort women became a collective national symbol of humiliation, a ‘demasculation’ of what had officially been portrayed as a masculine, patriarchal society in successful resistance to the Japanese.[47] The women’s uphill struggle for acknowledgment and compensation has resonated publicly, and some authors writing on this issue are themselves part of movements championing calls for bringing justice to these women.[48] These works have significantly enriched the literature by bridging military and social history, contributing to analyses of the relationship between power, imperialism, and gender to take a hold in the study of the war in Asia. All this also contributed to a strong victim-centred image of the ianfu [49] and the advocates for the comfort women’s cause have persistently allowed for the question of complicity of both the women’s families and that of local Korean or Chinese brokers in the recruitment process to be swept under the proverbial rug.[50] More recent studies by Erik Ropers or C. Sarah Soh added some much needed context and a fresh perspective. They place the use of comfort women in wartime Asia in the context of long-term licensed prostitution in Japan, and also pay attention to those women who hailed from Japan itself.[51]

The study of film, too, has contributed to addressing the difficult memories of collaboration. Ang Lee’s 2007 espionage erotic thriller Lust, Caution (色 | 戒) has proven a popular and fruitful case study, as its public reception and sanitization (both sexually and politically) for different Chinese markets illuminates colliding patriotic and diasporic sentiments in a post- war world of two Chinese national entities in which the events of World War Two still have emotional purchase.[52] Tsu, Wilson and Tam point out that war-related Chinese and Japanese feature films, documentaries, animes or TV dramas have – informed by political agendas of the relevant regimes – greatly influenced the public (re-) interpretation of the war through the decades. In the process they created long-living stock characters, such as the Mao-era ‘Japanese devil’, or addressed perennial issues in a divergent manner, like questions of responsibility for and justification of the war. Notably, Tsu et al. lament the lack of monographic treatment of Asian post-1945 war films, especially as art forms in their own right and subsumed by categories other than those provided by Hollywood.[53]

Southeast Asia on the fringes

While a sizeable body of literature exists on East Asia, research on war commemoration in Southeast Asia still remains on the fringes; in part perhaps since Asia’s memory boom unfolded there in a rather selective fashion.

Places, such as Burma or the Philippines, where the war utterly devastated the country and exacerbated violent inter-ethnic and inter-religious strife are still woefully underrepresented. Work done by Richard Taylor on Burma’s Armed Forces Day (Tatmadaw) illuminates the prominent part the military has played in the country’s post-war history as it attempts to forcefully hold the highly fragmented nation together.[54] Studies pertaining to war remembrance in the Philippines have placed an emphasis on US-Filipino international relations and looked at school textbooks and Bataan Day. The latter is widely commemorated in the US and in the Philippines by physical markers, ceremonies as well as athletic re-enactments. It tells of the ‘special relationship’ between the two countries allegedly forged on the battlefield, which since the end of war has – with interruptions – come to form the core of official nation-building efforts aimed at “the pursuit of democratic ideals”.[55] The Japanese occupation is portrayed as a ‘dark age’ and contrasted with the ‘golden times’ under American rule, a view that is now increasingly being challenged.[56]

War remembrance on the Malaysian peninsula has received significantly more scholarly attention. Oftentimes because Singapore serves as the symbol of Western imperialism’s downfall in Asia and because of the conflict’s significance for post-war nation-building. In Singapore, World War Two remembrance has been used to propagate an image of multiple ethnicities harmoniously joining forces across all social strata for the defence and development of the city-state.[57] Even though this resulted in tightly-controlled top-down simplification of the wartime narrative, alternative interpretations do exist. Cultural geographers, such as Brenda Yeoh and Hamzah Muzaini, have augmented existing historical analyses with a perspective that conceptualizes the politics of memory in spatial terms, operating with the increasingly popular concept of the ‘memoryscape’ and unearthing diverse voices ‘from below’.[58] However, works that use the analysis of Singapore’s memorialization efforts to marry colonial and post-colonial perspectives, or which apply a transnational approach that looks beyond the island’s immediate ‘hinterland’ are still in short supply.[59]

Even though Southeast Asia has not been at the epicentre of research on Asia’s memory boom, examples from Malaysia and Singapore show that there are indeed multiple forms of subaltern remembrance below the state’s radar. Crucially though, clashes over the interpretation of the wartime past in Asia is predominantly seen in terms of the unresolved disputes with its neighbours and the confrontational behaviour they are able to provoke. This is viewed as detrimental to the stability of the entire region – with a new war always a possibility.[60]

The difficulties of reconciliation

Many scholarly contributions have contemplated the reasons for the persistence of these tensions. Some propose that this is due to geopolitical mechanisms during the Cold War era and the strong (capitalist) influence exerted by Western countries, especially the United States. This view boils Asia’s ‘Memory Problem’ – as Schwartz and Kim call it [61] – down to a difference in historical contexts in which the evolution of certain ‘traditions’ of remembrance have been created, which then clash with other conflicting ones [62] – sometimes inevitably so, as Minxin Pei claims.[63] Other authors see it as a problem of clashing apology and reconciliation cultures, which ultimately renders meaningful communication about what ‘serious’ repentance actually entails and what appropriate compensations are supposed to look like, impossible.[64] Still others submit that the obstacles to reconciliation in the form of sustainable, durable peace and communion [65] are really found in institutional structures.[66]

Indeed, there are voices within the literature that call for taking into account distinctly local socio-political and economic factors that determined the very different ways in which remembrance of World War Two developed in Europe and Asia. However, this does not seem to have translated into a departure from or, at least, a critical reflection of taking Europe as the benchmark for how reconciliation ought to be achieved. Japan, so the popular argument goes, simply has to go down the same path as Germany – exhibit ‘serious’ remorse and fully embrace its former perpetrator role, own up to this profession of guilt and responsibility by inscribing this narrative into their education system, public museums and memorials, while also compensating its victims financially. However, this leaves aside the possibility that achieving ‘peace’ and ‘closure’ in the wars of/over memory might mean something markedly different from what is generally understood in Europe.[67]

Mikyoung Kim and Barry Schwartz are among the few who point out that we might also have to take into account significant ‘cultural’ differences, including those in the linguistic realm, when dealing with wartime guilt, shame, and responsibility for past wrongs. They suggest that reconciliation as pursued in Europe was successful there because it could build on a culture that allowed former perpetrators to “assuage their guilt only by apologizing for the rights they have violated, and having their victims accept those apologies as compensation for physical and mental suffering.”[68] By contrast, Asian societies, they argue, are ‘honour cultures’ where despite the prevalence of the official apology, [69] atonement is much more difficult to achieve. While these authors intentionally set up their arguments in highly generalizing and normative ways, this does not mean they should be completely discounted. This seems particularly called for, since a fair number of those actively engaged in the process of reconciliation in Asia appear unconcerned with potential cultural incompatibilities.

Of course, reconciliation processes are endeavours that require active engagement by both state and non-state actors. Falling back on Lily Gardner Feldman’s research, Andrew Horvat points out that antagonisms in Europe were not chiefly overcome because of what the different governments did, but because of efforts by non-governmental organisations, which also operated transnationally.[70] ‘Reconciliation practitioners’ operate with a similar approach and believe that “the steady development of peace in Asia and the world [can be achieved] through communication, conversation, and collaboration”.[71] Scholars in and outside of Asia are heavily involved in attempts to initiate such undertakings. A few examples include the Memory and Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific programme, co-founded by historian Daqing Yang at George Washington University, or the Taiwan-based Minjian East Asian Forum. South Korean scholar Emilia Heo of Tokyo’s Sophia University is another recognised inter-state reconciliation expert who subscribes to the joint education approach. Moreover, in 2015, just in time for the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, Routledge will release a Handbook of Memory and Reconciliation in East Asia, edited by Mikyoung Kim.

While all these programmes and publications provide an intellectual forum for exchange for non-state actors, more ‘hands-on’ solutions to Asia’s Memory Problem include collaborative historical research projects, youth tours and jointly written school textbooks; measures inspired by similar instances between Germany and Poland, or Germany and France.[72] In Asia, such projects have begun to materialise as well, most notably between China, Japan, and South Korea. The latest and perhaps most promising of these was the publication of a trilaterally-produced textbook in May 2005, entitled The Modern and Contemporary History of Three East Asian Countries. This book employed a ‘reflective’ and integrative approach of writing, so as not to reproduce a ‘victor-victim’ dichotomy familiar from existing textbooks in these countries.[73] While undoubtedly a laudable achievement, continuing tensions over wartime narratives, and the very fact that this publication was not made compulsory reading in schools, make these efforts appear short-lived and of limited success, if not outright fruitless.[74] Emilia Heo furthermore cautions us to blindly apply certain approaches to Asia that have worked in Europe. While she stresses the importance of civil society action as well, she points out the limits of inter-religious dialogue in reconciliation efforts between South Korea and Japan, for example.[75]

If we train our eyes on other efforts, namely commercial ones, we might find means by which new routes to reconciliation can also be forged. Tourist enterprises, such as the new Flying Tigers Heritage Park in the southern Chinese city of Guilin, opened in March 2015, is probably the most recent case in point. In cooperation with the regional authorities of Guangxi Province, it was set up by the Flying Tigers Historical Organization, a coalition of American and Chinese travel agents, military veterans, and amateur historians. They seek to promote friendly international relations by means of commercialised and globalised conflict heritage.[76] But instead of outright discarding commercialised efforts such as these – as has been done by critics of heritage or war tourism before – this might in fact be a topic worth exploring.[77]

Conclusion

This leaves us with the difficult question of how to proceed from here, as researchers, teachers, students, or ‘practitioners’. As we have seen, the commemorative landscape of Asia is characterised by extremely uneven terrain. In East Asia, public engagement with World War Two is already at an all-time high, whereas in Southeast Asia many wartime memories have been transformed beyond recognition, or remain silenced and removed from the public eye, perhaps waiting for the eventual ‘boom’ they deserve. While a look at media coverage might often suggest that Asia’s memory boom is predominantly fuelled by governmental action, we need to remind ourselves that hidden commemorative sites and practices, run by those outside or even in direct opposition to the relevant local political hierarchy, are an important part of this phenomenon.

Paying more attention to non-state actors (and their interactions with the state) will give us the opportunity to look at memory-constructs that might arguably be more relevant for many people than the purely state-prescribed forms and contents of an imagined nation. It might allow us to unearth narratives suppressed or marginalized by the latter, like the memory of the romusha in Southeast Asia. Especially interesting might also be remembrance at the very private level of the family, which has thus far been woefully under-researched. Such voices partly make an appearance already as part of larger oral history projects, like the Hong Kong Memory Project, which suggest fruitful ways of engaging with these actors.[78]

Not only could we profit from a new micro-perspective, but a macro-perspective on the transnational level holds equal promise for enhancing our understanding of how war and conflict is remembered and for what purpose. If we take into consideration the fact that the productions of collective memories and its carriers do not stop at the geographical boundaries of different nation-states, it will become clear how remembrance of the war in Asia is connected in many ways, despite its copious and differing local legacies.[79] Peace museums and heritage parks are often multi-national endeavours, with local project leaders but foreign design companies, for example. But can investigation of the globalization of exhibition practices and remembrance narratives indeed reveal how the complications brought about by the violent dissolution of empires in Asia are tied up with the impact of global capitalism, which now seems to have been widely accepted as East Asia’s most viable/only path to ‘modernity’? [80]

Another connected avenue of future research is one that leads us to the role of religion in reconciliation processes. It is still barely understood what role different religions in Asia play in the commemoration process beyond providing the parameters for burial practices and rituals of mourning. Since some proven European models of conflict resolution have already been put to the test in Asia, but have either foundered or had limited success, it might be worth revisiting this strategy in light of new findings. The research recently undertaken by Tim Winter on the Euro-centrism in heritage conservation should urge us to first ask: What are the elements that are more relevant and more applicable in an Asian context? [81] What we find might allow us to pave new and more meaningful routes to reconciliation.[82]

Bibliography

Allen, M. and Sakamoto, R., ‘War and Peace: War Memories and Museums in Japan’, History Compass, 11/12 (2013): 1047-1058.

Assmann, A., ‘Canon and Archive’, in A. Erll and A. Nünning (eds.), Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2008) 97-107.

Assmann, A. and Conrad, S. (eds.), Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Assmann, J., Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 34-41.

Bayly, C.A. and Harper, T., Forgotten Wars: The End of Britain’s Asian Empire (London: Allen Lane, 2007).

Bayly C.A. and Harper, T., Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945 (London: Penguin, 2004).

Bisht, P., ‘The Politics of Cosmopolitan Memory’, Media, Culture & Society, 35/1 (2013): 13- 20.

Blackburn, K. and Hack, K., War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press, 2012).

Blackburn, K., ‘War Memory and Nation-Building in South East Asia’, South East Asia Research, 18/1 (2010): 5-31.

Blackburn, K. and Hack, K. (eds.), Forgotten Captives in Japanese Occupied Asia (London: Routledge, 2008).

Brooks, T., ‘Angry States: Chinese views of Japan as seen through the Unit 731 war museum, 1949-2013’, Writing the War in Asia – a documentary history (March 2014), M.R. Frost, D. Schumacher (eds.), URL=<http://www.uni-konstanz.de/war-in-asia/brooks/>, accessed on 21 June 2014.

Buruma, I., The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1994).

Callahan, M.P., Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

Carr, G. and Reeves, K. (eds.), Heritage and Memory of War: Responses from Small Islands (New York: Routledge, 2015).

Chang, H.-H., ‘Transnational Affect: Cold Anger, Hot Tears, and Lust, Caution’, Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies, 35/1 (2009): 31-50.

Chang, I., The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

Chen, K.-H., Hu, C.-Y., and Wang, C.-M., ‘Minjian East Asia Forum: Feelings and Imaginations’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 14/2 (2013): 327-333.

Chen, K.-H., Hu, C.-Y., and Wang, C.-M., ‘Facing History, Resolving Disputes, Working Towards Pease in East Asia: A Statement by the Minjian East Asia Forum’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 14/2 (2013): 334-338.

Chirot, D., Shin, G.-W., and Sneider D. (eds.), Confronting Memories of World War II: European and Asian Legacies (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014).

Coble, P., Facing Japan: Chinese Politics and Japanese Imperialism, 1931-1937 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1991).

Cochrane J. (ed.), Asian Tourism and Change (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008).

Cohen, P.A., ‘The Burden of National Humiliation: Late Qing and Republican Years’, in idem, Speaking to History: The Story of King Guojian in Twentieth Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 36-86.

Cornelißen, C. et al. (eds.), Erinnerungskulturen: Deutschland, Italien und Japan seit 1945 (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2004).

Daase, C., ‘Addressing Painful Memories: Apologies as a New Practice in International Relations’, in A. Assmann and S. Conrad (eds.), Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 19-31.

Denton, K.A., ‘Horror and Atrocity: Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums’, in C-.K. Le, G. Yang (eds.), Re-envisioning the Chinese Revolution: The Politics and Poetics of Collective Memories in Reform China, (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2007), 245-286.

Dirlik, A., ‘’Trapped in History’ on the Way to Utopia: East Asia’s ‘Great War’ Fifty Years Later’, in T. Fujitani, G.M. White, and L. Yoneyama (eds.), Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s) (Durham, North Carolina: Duke UP, 2001), 299-322.

Diamant, N.J., ‘Conspicuous Silence: Veterans and the Depoliticization of War Memory in China’, Modern Asia Studies 45/2, Special Issue: China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy (2011): 431-461.

Erll, A., ‘Travelling Memory’, Parallax, 17/4 (2011): 4-18.

Erll, A., Memory in Culture, transl. by Sara B. Young (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Fengqi, Q., ‘Let the Dead Be Remembered: Interpretation of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial’, in: W. Logan and K. Reeves (eds.), Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’ (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009), 17-33.

Finney, P., ‘The Ubiquitous Presence of the Past? Collective Memory and International History’, The International History Review, (2013): 1-30.

Fujitani, T., White, G.M. and Yoneyama, L. (eds.), Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s) (Durham, North Carolina: Duke UP, 2001).

Fukuoka, K., ‘Memory, Nation, and National Commemoration of War Dead: A Study of Japanese Public Opinion on the Yasukuni Controversy’, Asian Politics & Policy, 5/1 (2013): 27-49.

Gluck, C., ‘Operations of Memory: ‘Comfort Women’ and the World’, in Jager, S.M. and Mitter, R. (eds.), Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), 47-77.

Goodall, H., ‘Writing Conflicted Loyalties: An Indian Journalist’s Perspectives in the Dilemmas of Indian Troops in Indonesia, 1945’, in Writing the War in Asia – a documentary History, (March 2014), Mark R. Frost, Daniel Schumacher (eds.), URL=<http://www.uni- konstanz.de/war-in-asia/goodall>, accessed on 17 November 2014.

Hack, K. and Rettig, T., ‘Imperial Systems of Power, Colonial Forces and the Making of Modern Southeast Asia’, in idem (eds.), Colonial Armies in Southeast Asia (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 3-38.

Halbwachs, M., On Collective Memory, ed. and transl. by Lewis A. Coser (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Hall, C.M. and Tucker H. (eds.), Tourism and Postcolonialism: Contested Discourses, Identities and Representations (Abingdon: Routledge, 2004).

Harper, T., ‘A Long View on the Great Asian War’, in D. Koh W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 7-20.

Henderson, J.C., ‘Heritage Attractions and Tourism Development in Asia: A Comparative Study of Hong Kong and Singapore’, International Journal of Tourism Research, 4 (2002): 337-344.

Henderson, J.C., ‘Singapore’s Wartime Heritage Attractions’, Journal of Tourism Studies, 8/2 (1997): 39-49.

Henry, N., ‘Memory of an Injustice: The ‘Comfort Women’ and the Legacy of the Tokyo Trial’, Asian Studies Review, 37/3 (2013): 362-380.

Heo, S.E., Reconciling Enemy States in Europe and Asia (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Hirsch, M., The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

Hisashi, O., ‘In Search of a New Identity’, in R.T. Segers (ed.), A New Japan for the Twenty- First Century: An Inside Overview of Current Fundamental Changes and Problems (London: Routledge, 2008), 234-249.

Hitchcock, M., King, V.T., and Parnwell, M. (eds.), Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2010).

Hong L. and Huang, J., The Scripting of a National History: Singapore and Its Pasts (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008).

Horvat, A., ‘Obstacles to European Style Historical Reconciliation between Japan and South Korea – a Practitioner’s View’, in D. Koh W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 167-173.

Igarashi, Y., Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000).

Ileto, R.C., ‘World War II: Transient and Enduring Legacies for the Philippines’, in D. Koh W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 74-91.

Ismail, R., Shaw, B.J., and Ling, O.G. (eds.), Southeast Asian Culture and Heritage in a Globalising World: Diverging Identities in a Dynamic Region (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009).

Jager, S.M. and Mitter, R. (eds.), Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007).

Khong, Y.F., Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Dien Bien Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

Kim, H. S., ‘History and Memory: The “Comfort Women” Controversy’, Positions, 5/1 (1997): 73-106.

Kingston, J., ‘Awkward Talisman: War Memory, Reconciliation and Yasukuni’, East Asia, 24 (2007): 295-318.

Koh, D. W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007). Koh, E., Diaspora at War: The Chinese of Singapore between Empire and Nation, 1937-1945

(Leiden: Brill, 2013).

Kratoska, P.H. (ed.), Asian Labour in the Wartime Japanese Empire: Unknown Histories (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2005).

Kuehn, J., Louie, K. and Pomfret, D. (eds.), Diasporic Chineseness after the Rise of China: Communities and Cultural Production (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013).

Kushner, B., ‘Pawns of Empire: Postwar Taiwan, Japan and the Dilemma of War Crimes’, Japanese Studies, 30/1 (2010): 111-133.

Lan, S.-c., ‘(Re-)Writing History of the Second World War: Forgetting and Remembering the Taiwanese-Native Japanese Soldiers in Postwar Taiwan’, Positions, 21/4 (2013): 801-851.

Levy, D. and Sznaider, N., The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age, transl. by Assenka Oksiloff (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006).

Lim, P. P. H. and Wong, D. (eds.), War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore, ISEAS: 2000).

Lim, J.-H., ‘Victimhood Nationalism in Contested Memories: National Mourning and Global Accountability’, in A. Assmann, S. Conrad (eds.), Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 138-162.

Lloyd, D.W., Battlefield Tourism: Pilgrimage and the Commemoration of the Great War in Britain, Australia and Canada, 1919-1939 (Oxford: Berg, 1998).

Logan, W., and Reeves K. (eds.), Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’ (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009).

Loh, K.S., Dobbs, S. and Koh, E. (eds.), Oral History in Southeast Asia: Memories and Fragments (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Maca, M. and Morris, P., ‘Education, National Identity and State Formation in the Modern Philippines’, in E. Vickers and K. Kumar (eds.), Constructing Modern Asian Citizenship (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

MacKinnon, S.R., Wuhan, 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

Mitter, R., China’s War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival (London: Penguin, 2013).

Mitter, R. and Moore, A.W., ‘China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy: Introduction’, Modern Asian Studies, 45/2 Special Issue: China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy (2011): 225-240.

Mitter, R., ‘Old Ghosts, New Memories: China’s Changing War History in the Era of Post-Mao Politics’, in Journal of Contemporary History, 38/1 (2003): 117-131.

Mitter, R., ‘Behind the Scenes at the Museum: Nationalism, History and Memory in the Beijing War of Resistance Museum, 1987-1997’, The China Quarterly, 161 (2000): 279-293.

Moore, A.W., Writing War: Soldiers Record the Japanese Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013).

Moore, A.W., ‘The Problem of Changing Language Communities: Veterans and Memory Writing in China, Taiwan, and Japan’, Modern Asian Studies, 45/2 Special Issue: China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy (2011): 399-429.

Morris, P., Shimazu, N. and Vickers, E. (eds.), Imagining Japan in Post-war East Asia: Identity Politics, Schooling and Popular Culture (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013).

Müller, G. (ed.), Designing History in East Asian Textbooks: Identity Politics and Transnational Aspirations (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011).

Muzaini, H., ‘Sybil’s Clinic @ Papan: Remembering a Malaysian War Heroine’, Writing the War in Asia – a documentary history (March 2014), M.R. Frost, D. Schumacher (eds.), URL=<http://www.uni-konstanz.de/war-in-asia/muzaini/>, accessed on 1 July 2014.

Muzaini, H., ‘Scale Politics, Vernacular Memory and the Preservation of the Green Ridge Battlefield in Kampar, Malaysia’, Social & Cultural Geography, (2013): 1-21.

Muzaini, H. and Yeoh, B.S.A., Contested Memoryscapes: The Politics of Second World War Commemoration in Singapore (Farnham: Ashgate, , 2015, forthcoming).

Muzaini, H. and Yeoh, B.S.A., ‘Memory-Making ‘From Below’: Rescaling Remembrance at the Kranji War Memorial and Cemetery, Singapore’, Environment and Planning A, 39 (2007): 1288-1305.

Muzaini, H. and Yeoh, B.S.A., ‘War Landscapes as ‘Battlefields’ of Collective Memory: Reading the Reflections at Bukit Chandu’, Singapore’, Cultural Geographies, 12 (2005): 345- 365.

Nora, P., ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’, Representations, 26 Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory (1989): 7-24.

Pei, M., ‘The Paradoxes of American Nationalism’, Foreign Policy, (2003): 31-37.

Phillips, K.R. and Reyes, G.M. (eds.), Global Memoryscapes: Contesting Remembrance in a

Transnational Age, (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011).

Preston, P.W., National Pasts in Europe and East Asia (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010).

Reid, A., ‘Remembering and Forgetting War and Revolution’, in M.S. Zurbuchen (ed.), Beginning to Remember: The Past in the Indonesian Present, Singapore: Singapore UP, 2005, 168-191.

Reilly, J., ‘Remember History, Not Hatred: Collective Remembrance of China’s War of Resistance to Japan’, in Modern Asia Studies 45/2, Special Issue: China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy (2011): 463-490.

Richter, S. (ed.), Contested Views of a Common Past: Historical Revisionism in Contemporary East Asia (Frankfurt: Campus, 2008).

Rojas, C. and Chow, E. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Ropers, E., ‘Life on the Front Lines: Testimonies by Two Japanese ‘Comfort Women’’, Writing the War in Asia – a documentary history (July 2014), M.R. Frost, D. Schumacher (eds.), URL=<http://www.uni-konstanz.de/war-in-asia/ropers/>, accessed on 12 November 2014.

Runia, E., ‘Burying the Dead, Creating the Past’, History and Theory, 46 (2007): 313-325.

Schneider, C., ‘The Japanese History Textbook Controversy in East Asian Perspective’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 617 (2008): 107-122.

Schoppa, R.K., In a Sea of Bitterness: Refugees during the Sino-Japanese War (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011).

Schumacher, D., ‘‘Privates to the Fore’: World War II Heritage Tourism in Hong Kong and Singapore’, World History Connected, 11/1 (2014): <http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/11.1/schumacher.html>.

Schwartz, B. and Kim M., ‘Introduction: Northeast Asia’s Memory Problem’, in idem (eds.), Northeast Asia’s Difficult Past: Essays in Collective Memory (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 1-27.

Siegenthaler, P., ‘Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Guidebooks’, Annals of Tourism Research, 29/4 (2002): 1111-1137.

Soh, C.S., The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Soh, C.S., ‘Centering the Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Survivors’, Critical Asian Studies, 33/4 (2001): 603-608.

Soh, C.S., ‘Korean ‘Comfort Women’: Movement for Redress’, Asian Survey 36/12 (1996): 1227-1240.

Stahl, D. and Williams, M. (eds.), Imag(in)ing the War in Japan: Representing and Responding to Trauma in Postwar Literature and Film (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

Suzuki, S., ‘Overcoming Past Wrongs Committed by States: Can Non-state Actors Facilitate Reconciliation?’, in Social & Legal Studies, 21/2 (2012): 201-213.

Suzuki, S., ‘The Competition to Attain Justice for Past Wrongs: The ‘Comfort Women’ Issue in Taiwan’, Pacific Affairs, 84/2 (2011): 233-244.

Tam, K.-f., Tsu, T.Y. and Wilson, S. (eds.), Chinese and Japanese Films on the Second World War (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

Tamm, M., ‘Beyond History and Memory: New Perspectives in Memory Studies’, History Compass, 11/6 (2013): 458-473.

Tanaka, Y. and Young, M.B. (eds.), Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth-Century History (New York: The New Press, 2009).

Tanaka, Y., Japan’s Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation (London: Routledge, 2002).

Taylor, R.H., ‘The Legacies of World War II for Myanmar’, in D. Koh W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 60-73.

Togo, K., ‘Japan’s Historical Memory toward the United States’, in G. Rozman (ed.), U.S. Leadership, History, and Bilateral Relations in Northeast Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 17-43.

Togo, K., ‘Development of Japan’s Historical Memory: The San Francisco Pease Treaty and the Murayama Statement in Future Perspective’, Asian Perspective, 35 (2011): 337-360.

Tow, E., ‘The Great Bombing of Chongqing and the Anti-Japanese War’, in M.R. Peattie, Edward, J., and van de Ven, H.J. (eds.), The Battle for China: Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 256-282.

Twomey, C. and Koh, E. (eds.), The Pacific War: Aftermaths, Remembrance and Culture (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

van de Ven, H.J., War and Nationalism in China: 1925-1945 (London: Routledge, 2003). Varga, A., ‘National Bodies: The ‘Comfort Women’ Discourse and Its Controversies in South

Korea’, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 9/2 (2009): 287-303.

Vickers, E., ‘Frontiers of Memory: Conflict, Imperialism, and Official Histories in the Formation of Post-Cold War Taiwan Identity’, in Jager, S.M. and Mitter, R. (eds.), Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), 209-232.

Vickers, E., ‘Re-writing Museums in Taiwan’, in Shih, F.-l., Thompson, S. and Tremlet, P.-F. (eds.), Re-writing Culture in Taiwan (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009), 69-101.

Vickers, E. and Jones, A. (eds.), History Education and National Identity in East Asia (New York: Routledge, 2005).

Wang, G., ‘Opening Remarks’, in D. Koh W. H. (ed.), Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia (Singapore: ISEAS, 2007), 3-6.

Wang, G., ‘Memories of War: World War II in Asia’, in P. Lim P. H. and D. Wong (eds.), War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore, ISEAS: 2000).

Wang H.-l., ‘War and Revolution as National Heritage: ‘Red Tourism’ in China’, in P. Daly and T. Winter (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Heritage in Asia (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 218- 233.

Wang, Z., Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

Wang, Z., ‘Old Wounds, New Narratives: Joint History Textbook Writing and Peacebuilding in East Asia’, History & Memory, 21/1 (2009): 101-126.

Winter, J., ‘The Memory Boom in Contemporary Historical Studies’, Raritan, 21 (2001): 52- 66.

Winter, T., ‘Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20/2 (2014): 123-137.

Winter, T., Teo, P., and Chang, T.C. (eds.), Asia on Tour: Exploring the Rise of Asian Tourism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009).

Yoshiaki, Y., Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military during World War II (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

Zhang, Q. and Weatherley, R., ‘Owing up to the past: the KMT’s role in the war against Japan and the impact on CCP legitimacy’, The Pacific Review, 26/3 (2013): 221-242.

Notes

1 The author would like to thank his colleagues from the University of Hong Kong and the WARMAP project as well as the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions for improvement. The research for this article was made possible by a DAAD Research Fellowship and a Leverhulme Network Grant.

2 Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Wars, 7.

3 Wang, ‘Memories of War’, 19.

4 For some of the latest war memory-related controversies in Sino-Japanese relations as covered by certain press outlets, see Reuters in Beijing, ‘Beijing Seeks War Legacy Theme for Germany Visit’, South China Morning Post, 24 February 2014; Reuters, EPA, and Agence France-Presse, ‘Anger at Abe’s War Shrine Offering”, South China Morning Post, 15 August 2014; E. Li, ‘Old Fears’, South China Morning Post, 4 June 2014; N. Hayashi and A. Nakano, ‘Abe returns to hard-line approach in response to Beijing, Soul’, Asahi Shimbun, 24 April 2013, <http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/politics/AJ201304240082>, accessed 12 November 2014.

5 For an overview of the field of memory studies, see Tamm, ‘Beyond History and Memory’, 458-473.

6 Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies.

7 Mitter and Moore, ‘China in World War II, 1937-1945’, 225.

8 Moore, ‘The Problem of Changing Language Communities’, 399-429.

9 Morris, Shimazu and Vickers, Imagining Japan in Post-war East Asia, 5.

10 This is in line with the way in which Hack and Rettig (‘Imperial Systems’, 25f.) conceptualise Japanese imperial penetration in twentieth century Asia by using a three-circle model.

11 It should be noted that this article provides a survey of the Anglophone literature on the topic, a body of work which is both vast and representative of the major discourses that, in part, also run through the relevant Chinese- or Japanese-language publications, for example.

12 See most recently, Goodall, ‘Writing Conflicted Loyalties’.

13 Fujitani, White and Yoneyama (eds.), Perilous Memories. See also Reilly, J., ‘Remember History, Not Hatred’. Carol Gluck operates with the term ‘terrains of memory’: Gluck, ‘Operations of Memory’.

14 For Burma, see Callahan, Making Enemies.

15 Lan, ‘(Re-)Writing History of the Second World War’.

16 Koh, Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia.

17 Hack and Rettig point out that recruitment of colonial soldiers or resistance fighters by both the Allies and Japan to aid in their respective war efforts had created forces well prepared to immediately challenge returning European powers in open resistance right after the war, but also to suppress other opposing communities domestically. This further contributed to decolonization but also to violent inter-ethnic strife. See Hack, Rettig, ‘Imperial Systems’, 26.

18 Harper, ‘A Long View on the Great Asian War’, 7-20.

19 The education sector in East Asia has been a popular and important subject of research. See Morris, Shimazu and Vickers, Imagining Japan in Post-war East Asia; Müller, Designing History in East Asian Textbooks; Vickers and Jones, History Education and National Identity in East Asia.

20 Jager and Mitter, Ruptured Histories.

21 See, for instance, Hitchcock, King, and Parnwell, Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia; Logan and Reeves, Places of Pain and Shame; Winter, Teo, and Chang, Asia on Tour; Ismail, Shaw, and Ling, Southeast Asian Culture and Heritage in a Globalising World; Cochrane, Asian Tourism and Change; Hall and Tucker, Tourism and Postcolonialism. See also Lloyd, Battlefield Tourism.

22 Gungwu Wang argues that ‘Southeast Asia’ as, since World War II, morphed from a geographical concept to a political, cultural, and most importantly an economic concept that has even been institutionalized by (the still expanding) Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). See Wang, “Opening Remarks”, 3-6.

23 Runia, ‘Burying the Dead, Creating the Past’, 321f. For the ‘memory boom’ in Europe, see Winter, ‘The Memory Boom in Contemporary Historical Studies’, 52-66.

Aaron Moore reminds us that before this surge in monuments and museums, publication of testimonies by the survivors of World War Two reached their zenith, as was the case with Japanese veterans, for example. See: Moore, ‘The Problem of Changing Language Communities’, 424.

24 Halbwachs, On Collective Memory; Nora, ‘Between Memory and History’; Hirsch,, The Generation of Postmemory; Levy and Sznaider, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age, 23-38.

25 Assmann, “Canon and Archive”, 97; Finney, ‘The Ubiquitous Presence of the Past?’, 23.

26 Levy and Sznaider, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age.

27 For the most recent one, also synthesising earlier findings and expanding them with new source material, see Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival, London: Penguin, 2013. An increasing number of studies have begun to critically revisit the wartime efforts of various political actors, including the important role played by the Guomindang. See van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China; Coble, Facing Japan; Zhang and Weatherley, ‘Owing up to the past’, 221-242.

28 Cohen, ‘The Burden of National Humiliation’.

29 Wang, Never Forget National Humiliation. Under Mao, the GMD’s anti-Japanese war efforts had been discredited in official canon while the achievements of the CCP were overemphasized, despite the fact that the latter paled in comparison. This meant that many soldiers or their families found themselves unable to organize or become relevant actors in public. See Mitter, ‘Old Ghosts, New Memories’; Diamant, ‘Conspicuous Silence’, 460.

30 Some authors focus on the civilian experiences of refugees or bombing victims or examine the personal accounts of former soldiers to answer the question of how individual participants in the conflict outside the political hierarchy made sense of experiences of extreme violence. See Schoppa, In a Sea of Bitterness; MacKinnon, Wuhan, 1938; Tow, ‘The Great Bombing of Chongqing and the Anti-Japanese War’; Tanaka and Young, Bombing Civilians; Moore, Writing War.

31 Xinhua, ‘China Plans National Days on Nanjing Massacre, Anti-Japanese War Victory”, China Daily, 25 February 2014, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-02/25/content_17304921.htm>, accessed on 27 February 2014; Xinhua, ‘Dates Set to Honor Victory, Mourn Nanjing’, China Daily, 27 February 2014, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2014-02/27/content_17310834.htm>, accessed on 27 February 2014; Levy and Sznaider, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age. For a critical reflection on Levy and Sznaider’s approach and an extra emphasis on the agency of individual actors in the production of ‘cosmopolitan memory’, see Bisht, ‘The Politics of Cosmopolitan Memory’. Iris Chang’s controversial book The Rape of Nanking, published in 1997, doubtlessly contributed to framing the Nanjing Massacre as Asia’s ‘forgotten Holocaust’ in contemporary popular memory.

32 Xinhua, ‘Countries with Memorial Day’, China Daily, 26 February 2014, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2014-02/26/content_17307759.htm>, accessed on 27 February 2014.

33 Lim, ‘Victimhood Nationalism in Contested Memories’.

34 Togo, ‘Japan’s Historical Memory toward the United States’; Hisashi, ‘In Search of a New Identity’. 38 Igarashi, Bodies of Memory.

35 Siegenthaler, ‘Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Guidebooks’; Togo, ‘Development of Japan’s Historical Memory’. For example, not all Japanese ‘peace museums’ pass on the state-prescribed narrative of a Japan victimised by the Allied (atomic) bombings and completely obscure the country’s role as an aggressive subjugator of much of Asia. The Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, for instance, massively expanded and reopened in 2000, tells a very different story. There, Japanese imperialism presents itself to the visitor as the principal factor that led to war in Asia and, eventually, to the highly destructive invasion and subsequent occupation of a ‘historically peace-loving’ Okinawa by US forces. See Allen and Sakamoto, ‘War and Peace’.

36 Togo, ‘Development of Japan’s Historical Memory’.

37 Since 1978, over a dozen Class A war criminals have been enshrined at Yasukuni. For analyses of the shrine and its significance in various respects in Japanese society and beyond, see Kingston, ‘Awkward Talisman’; Togo, ‘Development of Japan’s Historical Memory’; Fukuoka, ‘Memory, Nation, and National Commemoration of War Dead’.

38 The adjacent Yushukan Museum was also renovated in 2002 under Koizumi’s premiership and now boasts nationalistic propaganda that seeks to justify Japan’s wartime exploits as acts of both Asian liberation and self- defence, while, in post-9/11 style, classifying Chinese resistance as an act of ‘terrorism’. See Kingston, ‘Awkward Talisman’; Fukuoka, ‘Memory, Nation, and National Commemoration of War Dead’.

39 Li, ‘Old Fears’, South China Morning Post, 4 June 2014.

40 Hayashi, N., ‘Mitsubishi Materials to Offer an Apology, Compensation to Wartime Chinese laborers’, Asahi Shimbun, 24 July 2015, <http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/social_affairs/AJ201507240052>, accessed on 25 July 2015.

41 Suzuki, ‘The Competition to Attain Justice for Past Wrongs’, 225f.

42 Vickers, ‘Frontiers of Memory’; idem, ‘Re-writing Museums in Taiwan’. This park and museum commemorate the GMD’s violent crackdown on Taiwanese protesters on 28 February 1947 and the subsequent period of ‘White Terror’.

43 Pan, ‘Sunday Event to Mark Taipei Air Raid’, Taipei Times, 29 May 2015, <http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2015/05/29/2003619431>, accessed on 1 August 2015.

44 Kim, ‘History and Memory’, 90.

45 Henry, ‘Memory of an Injustice’.

46 See, for example, the 1999 films Silence Broken: Korean Comfort Women or Habitual Sadness: Korean Comfort Women Today, as discussed in Soh, ‘Centering the Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Survivors’. See furthermore: Soh, “Korean ‘Comfort Women’’. The Korean women activists were later joined by Taiwanese, Chinese, Filipino, Dutch, and other women who had been forcibly recruited into sexual servitude.

47 Varga, ‘National Bodies’, 293f.; Kim, ‘History and Memory’, 94. See also Suzuki, ‘The Competition to Attain Justice for Past Wrongs’. See furthermore Gluck, ‘Operations of Memory’.

48 See, for example, Tanaka, Japan’s Comfort Women; Yoshiaki, Comfort Women.

49 The comfort women literature also extends into a field that focuses on the war crimes committed in occupied Asia more generally and issues of transnational justice. See Kushner, ‘Pawns of Empire’. See also Barak Kushner’s ongoing ERC project on war crimes and empire at Cambridge University or Kerstin von Lingen’s Junior Research Group on transcultural justice and the East Asian War Crimes Trials (1946-1953) at the University of Heidelberg.

50 Associated Press, ‘Japanese Mayor Says Second World War ‘Comfort Women’ Were Necessary’, The Guardian, 14 May 2013. Similar issues apply to discussions over the body count of the Nanjing Massacre or the conducting of biological and chemical experiments on prisoners by Japan’s infamous Unit 731. See Fengqi, ‘Let the Dead Be Remembered’; Brooks, ‘Angry States’.

51 Japanese comfort women had also been the first to publicize their experiences shortly after the end of war. Ropers, ‘Life on the Front Lines’; Soh, The Comfort Women.

52 Chang, ‘Transnational Affect’; Kuehn, Louie and Pomfret, Diasporic Chineseness after the Rise of China.

53 Tam, Tsu and Wilson, Chinese and Japanese Films on the Second World War, 1-11. See furthermore: Stahl and Williams, Imag(in)ing the War in Japan; Rojas and Chow, The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas.

54 Taylor, ‘The Legacies of World War II for Myanmar’, 70.

55 Blackburn, ‘War Memory and Nation-Building in South East Asia’, 17. See also, Maca and Morris, ‘Education, National Identity and State Formation in the Modern Philippines’.

56 Ileto, ‘World War II: Transient and Enduring Legacies for the Philippines’.

57 See, for example, Hong and Huang, The Scripting of a National History; Lim and Wong, War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore; Blackburn and Hack, War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore.

58 They define memoryscapes as the manifestation of “the manipulation of the past via space”, something profoundly unstable and dynamic. See Muzaini and Yeoh, ‘War Landscapes as ‘Battlefields’ of Collective Memory’, 346. For their ‘politics of scale’-approach, see Muzaini, ‘Scale Politics, Vernacular Memory and the Preservation of the Green Ridge Battlefield in Kampar, Malaysia’; Muzaini and Yeoh, ‘Memory-Making ‘From Below’’. For their latest work, see Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes. For the latest endeavour attempting to further the concept of the memoryscape, yet remaining rather vague in doing so, see Phillips and Reyes, Global Memoryscapes.

59 Schumacher, ‘Privates to the Fore’. Ernest Koh’s recent look at the wartime memories of Chinese diasporas in Malaya attempts to break free of the literature’s continuing focus on post-colonial memory-making which, he argues, often results in the unreflective adoption of state-conceived framings of the past. See Koh, Diaspora at War. For further attempts to unearth these alternative framings as employed by non-state actors, see Loh, Dobbs and Koh, Oral History in Southeast Asia.

60 Suzuki, ‘The Competition to Attain Justice for Past Wrongs’, 225. See also Parker, C.B., ‘Nationalism Clouds WWII Memories in Asia, Says Stanford Scholar’, Stanford News, 4 April 2014 <http://news.stanford.edu/news/2014/april/memory-war-asia-040414.html>, accessed on 1 November 2014.

61 Schwartz and Kim, ‘Introduction: Northeast Asia’s Memory Problem’, 2, 23.

62 Chen, Hu, and Wang, ‘Minjian East Asia Forum’; idem, ‘Facing History, Resolving Disputes, Working Towards Peace in East Asia’; Khong, Analogies at War.

63 Pei, M., ‘The Paradoxes of American Nationalism’.

64 Schwartz and Kim, ‘Introduction: Northeast Asia’s Memory Problem’.

65 Emilia Heo defines this as the bringing together and mutual understanding of two dyads. See Heo, Reconciling Enemy States in Europe and Asia, 68. Therefore, practitioners see the most promising route to reconciliation to lie in joint projects that assist both sides to understand each other’s perspective on a certain event. They thereby seek to promote lasting peace or at least the willingness of the dyads in questions to resort to another armed confrontation.

66 Horvat, ‘Obstacles to European Style Historical Reconciliation between Japan and South Korea.’ However, Horvat himself proposes to bring in help from transnational non-state actors from outside of Korea, for example.

67 Here, deeper analysis of the role of Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and Shinto believes in the practices of remembering violent mass death and how they conceptualise the relationships between the dead and the living would be enlightening.

68 Schwartz and Kim, ‘Introduction: Northeast Asia’s Memory Problem’, 6.

69 Daase, ‘Addressing Painful Memories’.

70 Horvat, ‘Obstacles to European Style Historical Reconciliation between Japan and South Korea’, 153. 82 Chen, Hu, and Wang, ‘Facing History, Resolving Disputes, Working Towards Peace in East Asia’, 334. 83 Heo, Reconciling Enemy States in Europe and Asia.

71 Chen, Hu, and Wang, ‘Facing History, Resolving Disputes, Working Towards Peace in East Asia’, 334.

72 Suzuki, ‘Overcoming Past Wrongs Committed by States’.

73 Wang , ‘Old Wounds, New Narratives’, 102.

74 Ibid.

75 Heo, Reconciling Enemy States in Europe and Asia.

76 Flying Tigers Historical Organization, ‘The Flying Tigers Historical Organization Mission Statement’, <http://www.flyingtigershistoricalorganization.com/about/mission-statement/>, accessed 2 August 2015.

77 Indeed, across East and Southeast Asia the tourism sector has grown into an important market for negotiating and transforming narratives of violent episodes of the past both on a national and international level. See, among others, Wang, ‘War and Revolution as National Heritage’; Henderson, ‘Singapore’s Wartime Heritage Attractions’; idem, ‘Heritage Attractions and Tourism Development in Asia’.

78 http://www.hkmemory.hk/index.html.

79 The literature has already begun to push into this field by bringing together studies on war remembrance in Europe and Asia and pursuing a transnational approach. See Chirot, Shin, and Sneider, Confronting Memories of World War II; Twomey and Koh, The Pacific War; Carr and Reeves, Heritage and Memory of War; Assmann and Conrad, Memory in a Global Age; Preston, National Pasts in Europe and East Asia; Cornelißen et al., Erinnerungskulturen. See also Buruma, The Wages of Guilt. For the idea of ‘travelling memories’, which can be useful in a transnational context, see Erll, Memory in Culture, 66; idem, ‘Travelling Memory’, 12f.

80 Chen, Hu, and Wang, ‘Facing History, Resolving Disputes, Working Towards Peace in East Asia’, 334.

81 Winter, ‘Beyond Eurocentrims?’.

82 Such routes are, among other things, currently being scrutinized by the ‘War Memoryscapes in Asia Partnership’ (WARMAP) at the University of Essex, in which the author is also involved.