The Enfranchising Dimension of Official War Commemoration in Hong Kong and Singapore

Daniel Schumacher, Researcher (History) at University of Essex

Introduction

Until the 1980s, the state in mainland China had largely abstained from providing official sites or practices commemorating the war against Japan. [1] At the same time, in adjacent territories a whole infrastructure of monuments and remembrance services was forged that was designed to pass on a clearly defined narrative of the Japanese invasion and occupation. Hong Kong and Singapore each represent a case in point. Yet, scholarship on remembrance of World War II has long failed to examine them together.

Both British colonies had been hit hard when the excesses of the war in China proper radiated beyond its borders. In December 1941 and February 1942 respectively, the British, Commonwealth and locally recruited troops defending these territories suffered shameful defeat at the hands of their Japanese opponents who subsequently established an occupational regime that left Hong Kong’s and Singapore’s populations deeply affected in a variety of ways. Of the British and Allied soldiers who were captured, many were sent to forced labour camps in places such as Japan, Taiwan, or on the infamous Siam-Burma Railway. [2] The civilians of Hong Kong experienced indiscriminate acts of violence, destitution and mass displacement to the mainland. The wartime experience of the civilians in Singapore was of a similar nature, but especially that of the Chinese community was inextricably bound up with mass executions as part of the so-called Sook Ching operation, an effort to purge Singapore’s population of all potential ‘anti-Japanese elements’, which were thought to reside among the Chinese first and foremost. [3]

Lim Bo Seng Memorial, Esplanade Park, Singapore (photo: author, Jan. 16, 2011)

At the same time, however, local guerrilla formations were also able to stage subversive action against the Japanese. On the Malayan peninsula, the Chinese dominated Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) and the British-led Force 136 played major roles in the armed resistance. In Hong Kong, this role chiefly fell to the Communist Chinese 東江縱隊 (dongjiang zongdui), or East River Column, which had first formed in adjacent Guangdong Province, and to the somewhat less significant British Army Aid Group (BAAG) which consisted largely of Westerners and anglicised Chinese who had escaped Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. These resistance formations received noticeable assistance from both Western and Asian civilians in the respective territories who, in turn, suffered punishment and retribution by the Japanese occupation forces. [4]

After Emperor Hirohito had announced Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, Britain swiftly returned to Hong Kong and Singapore to reinstall herself as a colonial power for reasons of prestige and strategic economic thinking. [5] The war against Japan, Britain’s swift defeat therein and the resistance efforts staged by the local populations had, however, radically changed the terms upon which the British could base their renewed claim to rule. [6] This would consequently extend into the means by which the war would publicly be remembered. In the 1920s, monuments and practices commemorating the First World War in Britain had been replicated and introduced in the colonies and were used as symbols of colonial hierarchy and dominance. London’s principal war memorial, the Cenotaph, and the associated practice of Armistice/Remembrance Day formed the basis for this infrastructure of war commemoration. [7] In the aftermath of the Second World War (now with a first-hand war experience to deal with), this infrastructure in Hong Kong and Singapore could not simply be ‘updated’ without commemorating to some extent the dead from among the local population as well.

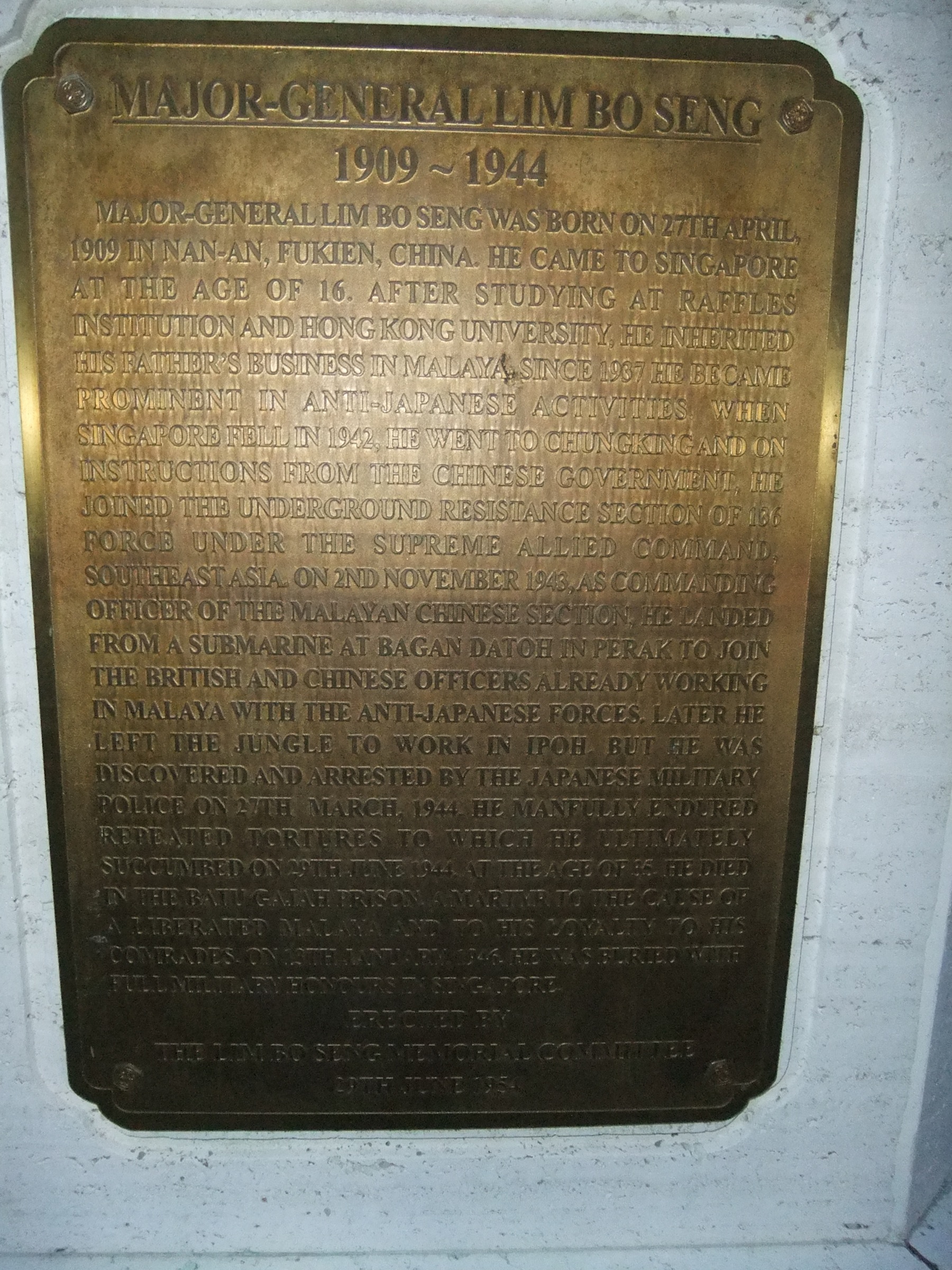

Affixed Bronze Plaque, Esplanade Park Singapore

Despite a post-war period charged with pro-reform sentiments and, at least in Singapore, even a willingness to work towards eventual self-government, [8] the British authorities still attempted to retain a firm grip on how the war years would be publicly remembered. Local agents were, however, far from powerless. Indeed, even in this politically sensitive field they were able to find ways to articulate their views on whom should be remembered and how. The volatile situation in the immediate post-war period had triggered the opening up of some of the British decision-making structures which certain local community leaders used as entry points to skilfully insert their calls for public representation of their communities’ war dead. Yet, these community leaders still had to work within the parameters laid out by the British authorities. These parameters included three principal components.

First, the sacrifices of all local ethnicities had to be portrayed as having been willingly rendered in the defence of the British Empire. Second, these acts of self-sacrifice had to be shown to somehow contribute to legitimatising post-war British rule, for instance by testifying to an anti-Japanese struggle that had been on-going throughout the occupation period. Third, those remembered also had to be politically tenable in a post-war environment which saw both Hong Kong and Singapore at the Asian frontlines of the Cold War.

Where these requirements were observed, it was possible to successfully challenge the official representation of the past. The state’s narrative could thus be perforated, augmented, or even partly or completely overwritten. [9] On the basis of two case studies, I will highlight this enfranchising dimension of public remembrance in Hong Kong and Singapore and how its repercussions partly shaped the way in which the war years are being publicly remembered today.

First, this paper will briefly illustrate efforts by Chinese interest groups in Singapore from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s to include the dead from among their midst into the official canon of remembrance. Second, it will look at Hong Kong in the 1980s and 1990s and how the locally organised Pacific War veterans used their wartime service and suffering as a means to repeal racially biased immigration legislation by London.

Chinese interest groups in Singapore

Among the communities most heavily affected by the Japanese occupation of Singapore were the Chinese. Diana Wong argues that their war experiences, coupled with the resistance effected against the Japanese, contributed to a growing attachment of local immigrant communities to their place of residence. [10] In the aftermath of the war, this made it desirable for a permanent marker of Singapore’s war dead to be erected in situ where the Chinese community could come together in collective acts of mourning and remembrance. [11]

Singapore Cenotaph, Esplanade Park Singapore

However, within this community, different interest groups had rather different notions of how this should be done. Former resistance fighters wanted their own wartime sacrifices or the ‘heroism’ of their leading figures to be acknowledged, while others took a more victim-centred approach and intended to provide a proper resting place and memorial for the thousands of civilians who had died forcible deaths. These approaches did not all result in success and thus illustrate the limits of the enfranchising dimension of official war commemoration in Singapore.

For example, the veterans of the MPAJA had initially had their exploits formally honoured by the returning British with medals and military parades, and thus seemed to have recommended themselves for inclusion in the official remembrance canon. [12] However, when MPAJA veterans violently clashed with police in February 1946 while demonstrating for February, 15 – the day Singapore had been surrendered in 1942 – to be adopted as a public holiday, they effectively disqualified themselves from further deliberations on how local resistance efforts should be most adequately commemorated in public. [13] For the colonial regime, portraying local agents as the sole victors while, at the same time, capitalising on Britain’s swift defeat in the beginning of the Pacific War was simply out of the question; even more so, if these local war heroes appeared all too ready to violently turn on the British ‘liberators’. Soon, the latter would have to face off against many of the MPAJA veterans in a full-blown insurrection in the jungles of Malaya. [14]

Shortly after the Japanese surrender and Britain’s return, another agent had unsuccessfully attempted to make use of the state-provided decision-making frameworks to lobby for the adoption of his commemoration proposals. [15] Influential community leader and chairman of the South Seas China Relief Fund Union, Tan Kah-kee, intended to have the human remains of Chinese civilians exhumed from mass graves to be properly re-buried and a special memorial erected “as a testimony to Chinese sacrifices during the war.” [16] The state-conceived Singapore War Memorial Committee of which he was a member, deferred this proposal on the grounds that the Committee had really hoped to agree upon a multi-ethnic memorial. [17] Indeed, Tan’s project would not be revived and brought to fruition until the end of British rule. Other agents were, however, more successful and were, indeed, able to tap into the enfranchising potential of official war commemoration.

When, in early 1946, Tan Kah-kee first approached the British Military Administration, the remains of one particular Japanese victim, namely prominent Chinese guerrilla leader Lim Bo Seng, had just been returned to Singapore and laid to rest by the authorities in an official act with full military honours. [18] Lim, formerly both a senior officer in the Nationalist Army and in the British clandestine Force 136, had been captured while on operations in Japanese-occupied Malaya, tortured and executed in an Ipoh prison. Following his body’s return to his former place of abode, Lim’s second-in-command, Colonel Chuang Hui-tsuan, who also ran the Singapore Chinese Massacred Appeal Committee, began lobbying for a hero’s memorial to Lim Bo Seng to be erected on the island. [19] Through an additional memorial committee, Colonel Chuang began raising money and enlisting support from the Chinese in Singapore. [20] This project eventually succeeded not due to its ability to do just this, but because of a different reason.

Civilian War Memorial Singapore

The colonial government’s plans for an all-encompassing, multi-ethnic memorial had foundered in the late 1940s due to widespread indifference by the general public. [21] Chuang was able to successfully exploit this fact and offer the authorities a ‘Singaporean hero’ who was politically tenable in the context of contemporary Communist insurrection in Malaya, could illustrate local trust in British leadership and could be presented as proof that Britain had not abandoned her subjects with the arrival of the Japanese after all. At the same time, the Chinese community could hold up Lim “as an example of a successful businessman and doting father who risked everything, putting zuguo (fatherland) above family and self”. [22] These values of loyalty and self-sacrifice, drawn from the Chinese cultural tradition, were identified as the most fitting traits for a ‘true Malayan’, as Chuang’s successor phrased it upon the monument’s unveiling in June 1954. [23]

Lim Bo Seng was, consequently, elevated to the status of a role model for the local Chinese community and quasi-national hero of their newly adopted fatherland. Architecturally, the memorial’s design was reminiscent of a victory monument that the Guomindang had allegedly built in Nanjing [24] and thus spelled out the context in which the campaigning Singaporean Chinese saw their anti-Japanese struggle – namely, not as a fight in the defence of the British Empire, but as an effort at protecting their homes on the Malayan peninsula while showing solidarity with the anti-Japanese fight in mainland China. In order to satisfy the British authorities, however, Chuang and his committee had to compromise as well. The memorial had to be reduced in size and stand in the vicinity of the Cenotaph which, as a purely British-conceived monument, would frame the former and symbolically leave the British with the upper hand in the fight over dominating official representations of the wartime past. [25]

If we look at these memorials today they are trumped both in size and official significance by the nearby Civilian War Memorial, underneath which are buried some 600 urns of cremated human remains from civilian mass graves exhumed after the end of British rule. This monument stands as evidence of a post-colonial emancipatory move undertaken by the government of independent Singapore in 1967. Then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew revived and merged the formerly abandoned multi-ethnic approach of the British with the erstwhile rejected victim-centred focus of Tan Kah-kee to make this monument into a new national marker. Every year on February 15 – the date originally favoured by the MPAJA veterans – a state-championed ceremony was to commemorate all the “men and women who were the hapless victims” [26] of the Japanese occupation, as Lee put it. Singaporeans were to take inspiration, not from an alleged self-sacrifice the dead had rendered in the cause of a foreign power, as the British had propagated it, but rather from a notion of common suffering which all local ethnicities, it was suggested, had undergone equally and which had ignited their strivings for a home free from any colonial rule whatsoever. [27]

The organised ex-servicemen of Hong Kong

Edwards leading rallying Hong Kong Veterans

While Singapore had achieved full independence by 1965 and its government was giving official war commemoration a decidedly victim-centred spin, public remembrance of the war in Hong Kong continued virtually unchallenged within the sacrifice-centred parameters laid out by the British until the early 1980s. The effects of decolonisation markedly changed this.

In 1981, London passed the British Nationality Act which dealt a mortal blow to the already weakened principal of ius soli, the legal feature which had previously defined British subjecthood. The Act made some 2.5 million people in Hong Kong, half of its population at the time, into British Dependant Territory Citizens who had no right to freely enter or take abode in the UK unless they obtained ‘settled’ status and fulfilled a five-year residency requirement first. [28] The 1981 Act marked the latest step in “Britain’s process of disengagement” [29] from its (former) colonies and was replete with racially biased undertones as the citizens of Britain’s ‘white colonies’ – Gibraltar and the Falkland Islands – had been given full British citizenship without any restrictions pertaining to their civic rights. [30]

Coupled with the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, the new legislation brought with it great uncertainties. Hong Kong had been at the front line of the Cold War in East Asia, and a Communist China assuming control over a British-run territory was bound to be the cause of worry, especially for those legally associated with Britain. However, having no option to migrate after the ‘handover’ should circumstances require it, was a situation that was utterly unacceptable to many, including the small band of Pacific War veterans living in Hong Kong.

These veterans had served in the war as British subjects and as such had fulfilled their duty to the British Crown. Their exploits had furthermore been utilised by the colonial authorities to craft a wartime narrative that told of a united Empire under British captainship. In Hong Kong, as in Singapore, the local troops’ deeds had been portrayed as having directly contributed to eventual victory over Japan and had subsequently been used to legitimate Britain reclaiming Hong Kong after the war. The Hong Kong veterans set out to expose this gaping discrepancy between the representation of their wartime service and suffering and the way it was actually being acknowledged by the governments in Hong Kong and London. The objective was to win back citizenship rights as the most appropriate means of honouring the survivors of the Pacific War. The way in which this goal was pursued also revealed how non-governmental pressure groups with seemingly insignificant leeway could successfully make their voices heard and realise long-term results.

Cartoon depicting one of Hong Kong's War Widows watching in frustration two representatives from the Conservative and Labour parties fighting over the passport issue with utter disregard for the widow and Union Jack they are trampling on. (SCMP May 1996)

The veterans utilised the official commemorative infrastructure to voice their demands by staging demonstrations on Remembrance Day at Hong Kong’s Cenotaph. [31] Moreover, they made one man the face of their campaign and thus created a public figure through whom they could effectively articulate and channel their demands. This man was Jack Edwards, a British ex-Prisoner-of-War who had made Hong Kong his permanent home and had married a Chinese woman. [32] His personal wartime story of torture and forced labour in Taiwan, as well as his ability for eccentric self-dramatisation, ensured continued coverage by the media in both Hong Kong and the UK, and successfully swayed public opinion in the veterans’ favour. [33] On the one hand, Edwards fell back heavily on familiar imperial rhetoric by presenting the soldiers defending Hong Kong has having “fought and suffered for honour, king and country.” [34] On the other hand, he broke with the authorities’ hitherto sacrifice-centred focus. He presented the surviving non-white servicemen, as well as their wives and even the war widows, as having been victimised not only during wartime through physical and psychological maltreatment by the Japanese, but also by the current British authorities, as the latest immigration laws had effectively deprived them of their legal security. In order to emphasise the latter’s ‘moral depravity’, Edwards set the veterans’ sufferings at the hands of the Japanese on a par with those of former inmates of concentration camps in Europe and with Chinese massacre victims in Nanjing. [35] He thus suggested that a similar logic of compensating ex-servicemen and their dependants for their sacrifices applied in this case as well.

Both Edwards’ imperial rhetoric and his ability to muster widespread public and even royal support made him a tolerable agent with whom the colonial government could align itself. [36] Together they could lobby London to repeal what some of Hong Kong’s politicians, such as Senior UMELCO [37] member Lydia Dunn, called “the mean and unworthy denial of the just claims of Britain’s most vulnerable and deserving nationals.” [38]

Cover of Edward's autobiographical account of his wartime internment. First released in English in 1988, a Japanese translation followed in 1992, entitled 'Kutabare, Jap Yaro!' ("Drop Dead, Jap!").

With Edwards enlisted as one of the spokespersons of the passport issue, the way the war and its non-white survivors were recognised and remembered became inextricably linked with the bigger issue of Britain’s colonial retreat from Hong Kong and the legacy it would leave behind. In the run-up to the British general elections of 1997, both the Labour and Conservative parties picked up on the issue’s potential for publicity and were eager to repay what former Governor Lord Wilson had termed “a debt of honour” [39]. Hence, Edwards saw his 15-year-long campaign meet with a successful conclusion in June 1996, when the remaining 28 war widows and wives of Hong Kong’s non-white ex-servicemen were awarded full British passports. [40]

While certainly a major acknowledgment of service and suffering of non-white military personnel, it did, at the same time, give the British parliament the excuse to marginalise a far bigger group by thus declaring the passport case closed. This group comprised the Indians residing in Hong Kong who were also British Dependent Territory Citizens or British Nationals Overseas. Even though their numbers ran in the thousands and they had been denied full British citizenship as well, they had failed to successfully make their voices heard. With the governments in both Beijing and Delhi also unwilling to recognise them as their own nationals, they had to face virtual statelessness after the ‘handover’. [41]

Conclusion

This paper attempted to show how various non-governmental agents in Hong Kong and Singapore were able to make use of and adapt for their own purposes an infrastructure of war commemoration originally created by the British authorities for the assertion of colonial hierarchy and control. The scope of action of the agents surveyed here had been largely contingent upon the parameters laid out by the British colonial governments. But if observed at least in part, public representation of the war years was able to be successfully challenged and, like a palimpsest, be re-crafted. Colonel Chuang Hui-tsuan’s efforts to have a hero’s memorial erected to his late commander, Lim Bo Seng, enabled, albeit selectively, the official recognition of Chinese contributions in the fight against the Japanese as well as the introduction of a different context in which it was perceived by some of the locals – namely, as a resistance effort to protect not a foreign Empire, but a newly adopted homestead into which the Second Sino-Japanese War had extended. The example of Jack Edwards’ campaign in 1980s and ‘90s Hong Kong illustrated how racially biased action by a seemingly overpowering London government could be successfully countered. The winning strategy was that of exposing officially propagated hypocrisies with the help of the mass media and of re-appropriating the very infrastructure that had promised the authorities control over its version of the past. Both case studies not only revealed some of the possible means by which seemingly powerless agents were able to challenge official canon, but also the marked need of certain marginalised groups to be appropriately acknowledged in public – be it massacred civilians, disenfranchised survivors, or fallen multi-ethnic troops.

Contributor

Daniel Schumacher holds a Ph.D. in Modern History from the University of Konstanz. He worked as a DAAD Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Hong Kong and currently coordinates the “War Memoryscapes in Asia Partnership" (WARMAP) at the University of Essex. His research interests include war memory and humanitarianism in Asia, as well as transcultural education. This contribution is derived from research conducted in the context of his dissertation on “Strategies of World War II Commemoration in Hong Kong and Singapore.” He can be contacted at schum.dan@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] cf. Diana Lary, The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 204. See furthermore the contributions of “Part II: Remembering China’s War with Japan” in Modern Asian Studies 45.2 (2011) Special Issue: China in World War II, 1937-1945: Experience, Memory, and Legacy.

[2] cf. Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack, eds., Forgotten Captives in Japanese Occupied Asia (London: Routledge, 2008).

[3] cf. Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack, War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2012); Philip Snow, The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese Occupation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

[4] For Hong Kong, see: Chan Sui-jeung, East River Column: Hong Kong Guerrillas in the Second World War and After (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009); Edwin Ride, BAAG: Hong Kong Resistance 1941-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981); Snow, Fall of Hong Kong, 174-205. For Singapore, see: Paul H. Kratoska, The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History (London: Hurst & Company, 1998); Akashi Yoji and Yoshimuri Mako, eds., New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, 1941-1945 (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2008). For a comprehensive account of the war in these and in adjacent theatres, see: Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper, Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941- 1945 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006).

[5] cf. Nicholas Tarling, Imperialism in Southeast Asia: ‘A Fleeting, Passing Phase’ (London: Routledge, 2001), 261, 263.

[6] cf. Wang Gungwu, “Memories of War: World War II in Asia,” in War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, eds. P. Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000), 19.

[7] For Hong Kong, see: Report by Assistant Archivist Mrs Robyn H. McLean, Subject: Cenotaph, August 9, 1978, Public Records Office Hong Kong, PRO/REF/080, 3; “Armistice Day Observance in Hong Kong,” South China Morning Post, November 12, 1924, 9.

For Singapore, see: “Armistice Day: Memorial Services at Cenotaph and Cathedral,” Straits Times, November 13, 1922, 10; Uma Devi et al., Singapore’s 100 Historic Places (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2002).

For a conceptual underpinning of how such commemorative sites and practices are negotiated in a trans-national, border-crossing context, see: Astrid Erll, Memory in Culture, transl. Sara B. Young (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 66.

[8] cf. C.M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819-2005 (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2009), 225.

[9] Such transformations can aptly be described by conceptualising collective memories as palimpsests. See: Jay Winter, “In Conclusion: Palimpsests,” in Memory, History, and Colonialism: Engaging with Pierre Nora in Colonial and Postcolonial Contexts, ed. Indra Sengupta (London: German Historical Institute London, 2009), 167-174.

[10] cf. Diana Wong, “War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore: An Introduction,” in War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, eds. P. Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000), 6.

[11] For Chinese death rituals in Singapore, their forms, purpose and significance, see: Tong Chee-kiong, Chinese Death Rituals in Singapore (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004).

[12] cf. Blackburn and Hack, War Memory, 114f.

[13] cf. Mountbatten War Dairies, Press Note, Subject: Court of Inquiry Findings on

Singapore Firing, February 19, 1946, National Archives Kew, WO 172/1802, 444.

[14] cf. Blackburn and Hack, War Memory, 115.

[15] cf. Ag. Secretary for Chinese Affairs, Singapore to H.P. Bryson, Under Secretary, Singapore, Memorandum, Subject: Singapore War Memorial, August 30, 1946, National Archives of Singapore, NA 871 81/45, 19. See furthermore: “Memorial to Chinese Fallen,” Straits Times, February 6, 1946, 4; Report of the Singapore War Memorial Committee, Appendix A, Subject: Synopsis of Suggestions Received from Associations and Individuals for the Singapore War Memorial, January 29, 1947, National Archives of Singapore, NA 871 81/45, 2.

[16] C.F. Yong, Tan Kah-kee: The Making of an Overseas Chinese Legend (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987), 302f.

[17] cf. Minutes of Third Meeting of the Singapore War Memorial Committee, October 15, 1946, National Archives of Singapore, NA 871 81/45, 65.1.

[18] cf. “Remains of Col. Lim Bo Seng Laid to Rest,” Straits Times, January 14, 1946, 3.

[19] cf. “Memorial Planned for Lim Bo Seng,” Straits Times, January 4, 1951, 5.

[20] cf. “Lim Memorial Approved,” Singapore Free Press, June 27, 1951, 8. For another theory arguing that the memorial’s funding had mainly been provided by the Nationalist government in Chongqing and, in part, by the British colonial government, see: Romen Bose, Singapore at War: Secrets from the Fall, Liberation & Aftermath of WWII (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2012), 395.

[21] cf. “The Cenotaph Plan Shelved,” Sunday Times, September 26, 1948.

[22] Blackburn and Hack, War Memory, 122.

[23] cf. “A General Unveils a Hero’s Pagoda: Example of ‘True Malayan’,“ Straits Times, June 30, 1954, 5.

[24] cf. “Agreement on Singapore Memorial to Lim Bo Seng,” Straits Times, May 29, 1952, 8. See, furthermore: “Pagoda Memorial for S’pore Hero,” Straits Times, July 10, 1952, 8; “War Hero’s Memorial,” Straits Times, November 3, 1953, 7.

[25] cf. “Agreement on Singapore Memorial to Lim Bo Seng,” Straits Times, May 29, 1952, 8.

[26] Lee Kuan Yew qtd. in: “Mothers Mourn Anew at Memorial,” Straits Times, February 16, 1967, 9.

[27] cf. Kevin Blackburn, “The Collective Memory of the Sook Ching Massacre and the Creation of the Civilian War Memorial of Singapore,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 73.2 (2000): 71ff.

[28] cf. Prakash Shah, “British Nationality and Immigration Laws and Their Effects on Hong Kong,” in Coping with 1997: The Reaction of the Hong Kong People to the Transfer of Power, ed. Werner Menski (Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, 1995), 86. The right of abode in the UK had, technically, already been taken away from these citizens with the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act. See: Rieko Karatani, Defining British Citizenship: Empire, Commonwealth and Modern Britain (London: Frank Cass, 2003), 1.

[29] John Swaine qtd. in: Robert Cottrell, The End of Hong Kong: The Secret Diplomacy of Imperial Retreat (London: John Murray, 1993), 186.

[30] cf. Kathleen Paul, “Communities of Britishness: Migration in the Last Gasp of Empire,” in British Culture and the End of Empire, ed. Stuart Ward (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 2001, 180-199; Kathleen Paul, Whitewashing Britain: Race and Citizenship in the Postwar Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997).

[31] cf. “Silent Protest by PoWs at Ceremony,” South China Morning Post, August 31, 1982; “War Veteran Takes Fight for Widows to Cenotaph,” South China Morning Post, November 15, 1993.

[32] cf. Fionnuala McHugh, “Edwards, Jack,” in Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography, eds. May Holdsworth and Christopher Munn (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012), 132; Caroline Knowles and Douglas Harper, Hong Kong: Migrant Lives, Landscapes, and Journeys (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 22-34.

[33] Especially the South China Morning Post (SCMP), Hong Kong’s principal English- language daily since 1903, and the Hong Kong Standard, founded as a pro-Chinese daily in 1949, readily gave a far-reaching voice to Edwards’ campaign. For the Hong Kong press and the significance of individual papers, see: Joseph Man Chan and Lee Chin-chuan, Mass Media and Political Transition: The Hong Kong Press in China’s Orbit (New York: The Guildford Press, 1991); Stephen Hutcheon, “Pressing Concerns: Hong Kong’s Media in an Era of Transition,” (discussion paper D-32 presented at the Joan Shorenstein Centre, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, September 1998).

[34] Jack Edwards qtd. in: “War Veterans Hold Cemetery Protest on ‘Day of Infamy’,” South China Morning Post, January 10, 1989.

[35] cf. Jack Edwards, Banzai, You Bastards! (London: Souvenir Press, 1994). This book was first published in 1988.

For the uncritical reiteration of this stance in the Hong Kong press, see: “Fighting to the Bitter End,” South China Morning Post, June 18, 1988; “Jack Remembers War in Unique Way,” Hong Kong Standard, July 14, 1988.

For similar coverage by the British and Australian press, see: “Japan’s ‘Final Solution’ for POWs,” The Weekend Australian, June 18, 1988; “Plot to Slaughter British PoWs,” Sunday Express, June 19, 1988; “Unveiled: One of War’s Most Harrowing Secrets,” Blackpool Evening Gazette, July, 1988; “Author Knew Life and Death of Camps,” South Wales Echo, September 7, 1988.

For the symbolic connection between the Holocaust and the Nanjing Massacre, see: Ian Buruma, “The Nanking Massacre as a Historical Symbol,” in Nanking 1937: Memory and Healing, eds. Fei Fei Li et al. (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2002), 7f.

[36] cf. “Charles ‘Sends a Message on Abode’,“ South China Morning Post, November 9, 1992.

[37] UMELCO stands for Office of the Unofficial Members of the Executive and Legislative Council. It was established in 1963 “to promote closer relations between the Unofficial Members of the two Councils and members of the public” and enable the latter to bring their views and concerns about public affairs to the Councillors more immediately. See: Steve Tsang, ed., Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1995), 214.

[38] Lydia Dunn qtd. in: “The Sound of Two Hands Clapping,” South China Morning Post, January 9, 1986.

[39] “Britain Faces New Passport Pressure“, South China Morning Post, June 6, 1996.

[40] This was codified by the Hong Kong (War Wives and Widows) (No 2) Bill on 12 July 1996. See: “Victory for Jack in Widows’ Rights Fight,” South Wales Echo, June 12, 1996; “Widows’ Joy as Men’s Sacrifice Is Recognised,” South China Morning Post, June 13, 1996; “Veteran Jack Marks His Victory with a Bang,” Hong Kong Standard, April 4, 1997; “HK Spouses Get Passports,” The China Post, April 8, 1997.

[41] Early on, Delhi had made clear that these approximately 6,000 Indians with British documents were Britain’s responsibility: “India Enters Row over HK Ethnic Minorities,” South China Morning Post, April 9, 1986. Beijing, in turn, would only grant Chinese citizenship to ‘Chinese compatriots’. See: Laurie Fransman, Fransman’s British Nationality Law, 2nd ed. (London: Fourmat, 1989), 440.