John Creer's report: The Guomindang guerillas of Japanese-occupied Malaya

Rebecca Kenneison (Essex), PhD Student

Page 1

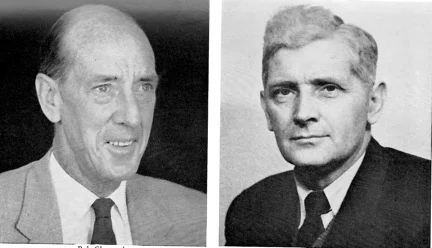

Robert Chrystal (left) and John Creer (right) in the 1950s

When the Japanese invaded Malaya in December 1941, resistance groups immediately sprang up to oppose them. The biggest of these was the communist-controlled and Chinese-dominated Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). Other, smaller groups existed: the Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Army (OCAJA, allied to the Chinese Nationalist party, the Guomindang) and, later, two Malay groups, Wataniah and the Askar Melayu Setia. Also in the jungle were small groups of Europeans in stay-behind parties trained by the Special Operations Executive’s Orient Mission to harass the Japanese behind their lines. [1] Many of these men, like other Europeans – such as game wardens – who had taken to the jungle during the retreat, were soon killed in action, dead from disease or captured by the Japanese. Those who survived inevitably came into contact with the guerrillas.

Once the SOE, in its Asian guise of Force 136, began to send operatives into occupied Malaya, their first contacts were with the MPAJA. Force 136’s aims in Malaya were principally the collection of intelligence, and the raising and arming of guerrilla forces to be used against the Japanese. To this end, they worked very closely with the MPAJA, which consistently represented all non-communist armed bands to them as ‘robbers’, including the OCAJA. [2] At least in part as a consequence of this, many of Force 136’s leading agents took a view of the OCAJA which has persisted into the historiography, where it is generally viewed as having been a loose coalition of bandit gangs which flew a political flag of convenience when it suited their purposes. [3]

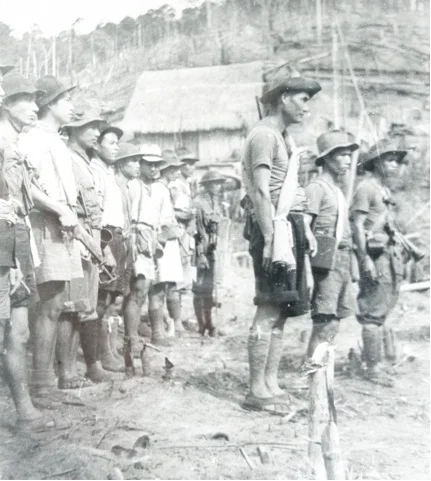

OCAJA detachment preparing to occupy Betong

Ranajit Guha argues that those outside an insurgent group will see it differently from those within it, and that maxim holds true as regards the OCAJA. [4] The MPAJA painted them in one light; John Creer’s report, written from within the OCAJA, paints them in quite another, thus broadening our perspective. Creer, an Oxford-educated member of the Malayan Civil Service was, in 1941, the District Officer at Kuala Trengannu on the east coast of Malaya, an area with a predominantly Malay population. [5] When the Japanese invaded in December 1941, he was cut off during the retreat and took the jungle rather than be taken prisoner. Often accompanied by one of Orient Mission’s stay-behinds, a rubber planter named Robert Chrystal, he spent time with both the MPAJA and the OCAJA in the uplands of the northern state of Kelantan.

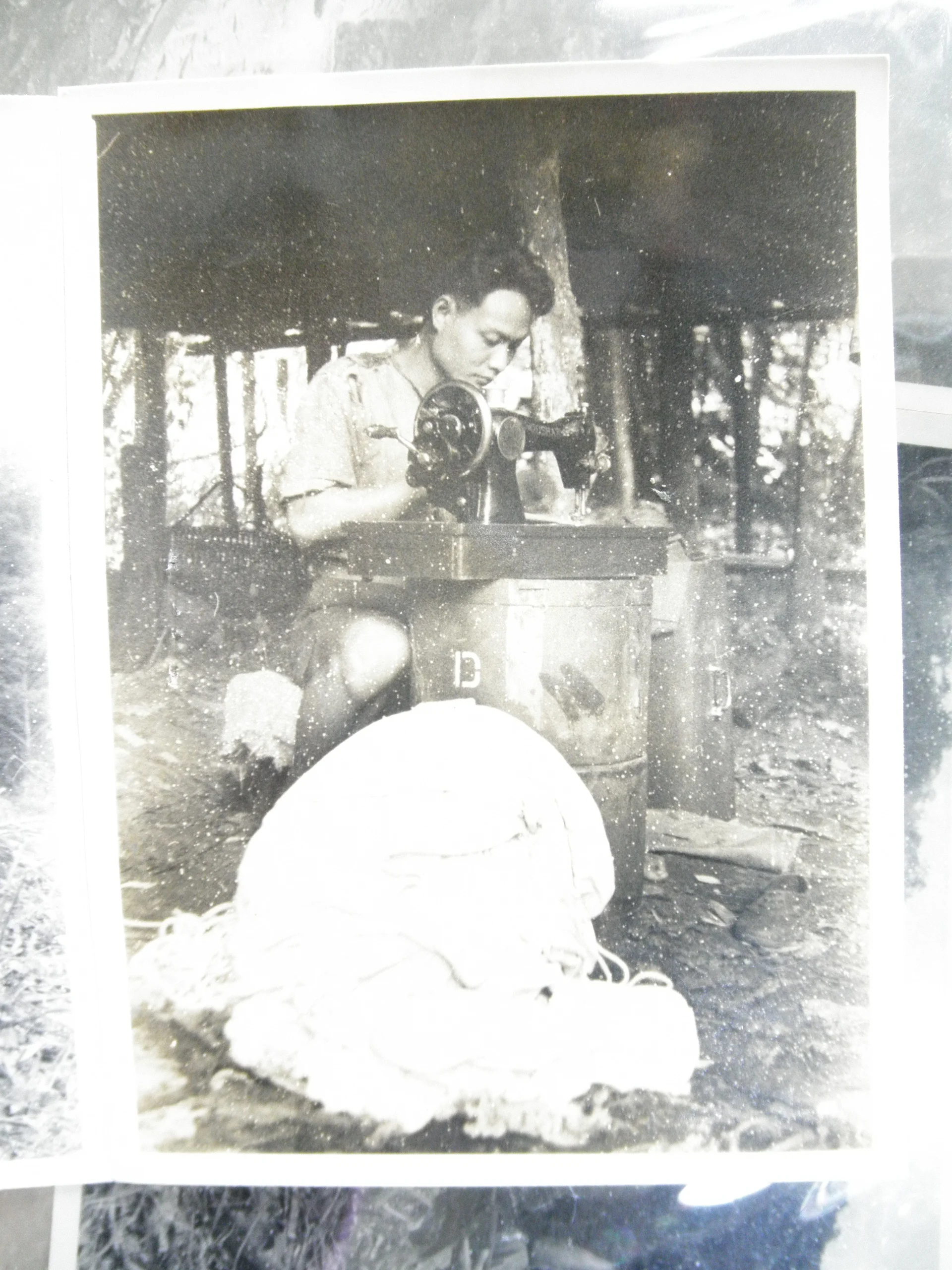

Towards the end of the war, these two men came into contact with Force 136, and worked with it until late in 1945. Not long after this Creer – like all the senior field operatives of Force 136 – wrote a report on his war-time activities. At 10,000 words, Creer’s report is exceptionally long, and it is not an easy read. However, it gives us a first-hand account of the activities of both groups of guerrillas, written soon after the events it describes. Creer appears to have been even-handed: he is critical of both the MPAJA and the OCAJA, though it is clear that he formed his friendships amongst the latter (who he refers to as the Kuomintang or KMT, in line with the transliteration used at the time). [6] What Creer has to say is strongly supported by other reports on the same file, and by the book The Green Torture: The Ordeal of Robert Chrystal, which is essentially the ghost written memoir of his companion. Parts of The Green Torture also provide valuable context for Creer’s report, describing as they do the administrative structures of the OCAJA who, amongst other things, established a permanent customs post on the edge of their territory and issued a paper currency underpinned by locally-panned gold. [7]

Parachutes being made into shirts in an OCAJA camp

From Creer’s report, three main themes emerge which have the power to change our view of Malayan political history. Firstly, he reveals – almost incidentally – just how strong a grip the OCAJA had in the western part of the state of Kelantan. He and Chrystal moved about freely, going on propaganda tours of Malay villages. [8] They were untroubled by bandits, for these had been summarily dealt with by the OCAJA. [9] For long stretches of the occupation, the Japanese hardly exist in Creer’s jungle: they raid along its edges and try to garrison small towns (where they are opposed by the OCAJA) but to an extent, the interior is decolonised, and Malayans are experimenting with self-rule. [10]

The second main theme is the ethnic nature of that self-rule. Creer’s report reveals a story of increasing racial cooperation: a group of ethnic Chinese, allied to a Chinese political party, controlled an area which had an almost entirely Malay population. Slowly, from a very poor start, the two groups came to a cooperative understanding, with the OCAJA working closely with an influential Malay headman and even recruiting Malays into their ranks by the end of the war. [11] The relationship was often difficult, and it is possible that the cooperation between the two groups was a consequence of the social geography of Kelantan: the OCAJA had only a few Chinese to turn to for support, and so were forced to look to the Malays, and the Malays, due to the OCAJA’s domination of this remote and mountainous district, had just as little choice. Whatever the reasons, however, the OCAJA’s eventual relationship with the Malays stands in contrast to the MPAJA’s. The Malays were traditionally unsympathetic towards communism, regarding it as contrary to their Muslim faith; further, the MPAJA generally regarded the Malays as stooges of the Japanese: almost all the MPAJA’s fighters, and about 90% of its support network, were Chinese. [12] In the second half of 1945, ethnic conflict broke out between the Chinese and the Malays in the western states of Malaya. The MPAJA entered it on the side of the Chinese and, whatever the rights and wrongs of their stance, it further convinced the Malays that communism was a Chinese creed. [13] Chinese dominance of the MPAJA would have serious consequences for the Malayan Communist Party during the Malayan Emergency: the communist insurgents were forever cut off from the support of more than half of the population, which preferred to work with and for the colonial power to crush the insurgency, while simultaneously negotiating for independence.

Kelanatan and the 'Kuomintang state' showing the possible extent of the 'state' after MPAJA incursions

The third – and perhaps most significant – story to emerge from Creer’s report concerns the relationship between the OCAJA and the MPAJA, which took exactly the opposite trajectory to that between the OCAJA and the Malays. Early in the occupation, the two groups worked together. However, the communists sought to convert the OCAJA, and when their endeavours were resisted, they tried to suborn groups of guerrillas; when they were again thwarted, a violent struggle for supremacy broke out. [14] According to Creer, the MPAJA had behaved in the same way elsewhere in Malaya: to him, the events in Kelantan were not merely localised difficulties but part of a larger pattern, whereby the communists strove to exert their hegemony across the Malayan interior. [15] To begin with, both sides were held back by shortages of arms and ammunition. Early in 1945, however, the MPAJA acquired armaments from Force 136 to use against the Japanese. It didn’t take them long to turn these on the OCAJA, who were driven relentlessly north as the year progressed (see map). This allowed the Japanese to penetrate far deeper into Kelantan than had previously been the case. [16] The Japanese were not putting down anarchy: they were taking advantage of a savage political war.

In sum, what Creer tells us challenges our views of three distinct issues. He shows us, very clearly, that the OCAJA were guerrillas, not bandits, controlling territory and resisting the Japanese. He indicates that inter-ethnic cooperation was possible at a time when ethnic strife broke out elsewhere in Malaya. Most significantly, he shows us that the roots of the Emergency lie within the Japanese occupation. Viewed from this perspective, the Malayan Emergency looks less like a spontaneous rising against imperialism and more like a reassertion of a long-standing ambition. This is not to deny the anti-imperialist aspect of the Emergency, but it does indicate that the Malayan communists had begun to position themselves for control of the interior even before the end of the Japanese occupation, long before the Emergency began.

Contributor

Rebecca Kenneison is a PhD student at the University of Essex. She has previously published ‘Playing for Malaya: A Eurasian Family in the Pacific War’ (NUS Press, 2011). Her current research focuses on the role of Force 136 (a branch of the Special Operations Executive) in Malaya during World War II and the intelligence it gathered.